The transit-first (no, really) games

In the end, LA28 put the events where the public transportation will already be

The Wim Wenders film Perfect Days follows Hirayama, a blue jumpsuit-wearing toilet cleaner, as he maintains public bathrooms tucked into leafy corners of Tokyo. Quintessentially Wenders — where are my Paris, Texas fans? — it's a stunningly beautiful portrait of the quiet intimacy found in busy cities, the critical importance of accessible infrastructure, and, more than anything, the people who care for the civic spaces that host our most vulnerable moments. It's also a commercial for 17 very real bathrooms built for the 2020 Tokyo Summer Olympics.

In the lead up to the games, The Tokyo Toilet erected a dozen public bathrooms in an epic collaboration between toilet manufacturer Toto, prefab company Daiwa House, the Nippon Foundation, and Koji Yanai, an executive at and heir to the Uniqlo fashion empire. But when the pandemic forced the games to be staged a year late and without spectators, Yanai contacted Wenders in the hopes he might drum up some publicity for the toilets to make up for the lack of social-media impressions. (Yanai is also an executive producer for the film.) The campaign worked — the film was Oscar-nominated in the international category and the phenomenal Koji Yakusho won best actor at Cannes — and on the award circuit a delightful Wenders has turned into a kind of public bathroom spokesperson, gamely fielding questions on toilet significance in Tokyo society. Because, to be clear, Perfect Days is branded content for Tokyo, a chance for the city to globally distribute its own civic propaganda after getting shortchanged on its Olympic moment. And in that sense, the film is an absolutely brilliant piece of tourism marketing. What could be more welcoming than a pretty place to pee?

The toilets themselves are lovely, designed by a famous and mostly Japanese roster of architects. The best known are a pair of bathrooms in Yoyogi Park designed by Shigeru Ban, glowing lanterns of translucent glass that cleverly turn opaque when occupied. My favorite are the Shoto Park bathrooms featured in the first scene of the film: fort-like clusters of vertically planked cedar designed by Kengo Kuma, who also designed the cedar-eaved Japan National Stadium for the 2020 (actually 2021) games. But I found myself more visually riveted by Hirayama's cleaning rituals; at one point he carefully examines the underside of the toilet's rim with a mirror. The actual Tokyo Toilet partnership includes maintenance, and the website, which is as well-produced as the film, goes into great detail about the frequency and intensity of cleaning — toilets are serviced three times a day! — as well as an oversight system by third-party inspectors who evaluate the cleanliness using a "contamination index."

Honestly, this is the part that got to me — I don't just want architecturally significant bathrooms built for the Olympics, I want a contamination index! But as residents of the notorious public toilet desert of Los Angeles, with 14 public toilets for 4 million residents, can we forge a path to better potties? I immediately called my go-to public toilet expert. (Yes, I have a go-to public toilet expert.)

Francois Nion is executive vice president of the French street-furniture company JCDecaux, which, until recently, held the city of LA's contract for public bathrooms (and bus shelters, but we'll get to that story another day). In fact, I caught Nion when he was in San Francisco, where he's been busy installing 25 new public bathrooms at no cost to the city. Next he'll be headed to Paris, where JCDecaux has installed over 435 public toilets, 200 of which will be upgraded to a new higher-capacity design in time for this summer's Olympics, also at no cost to the city. That's correct: JCDecaux pays for the toilets and servicing in exchange for the right to erect advertising kiosks in a city's public spaces. (We'll get to that story another day too.)

Nion loved Perfect Days, but he got anxious imagining the upkeep costs for 17 unique bathrooms, all with different site conditions, materials, and finishes to repair. "What we do is industrial well-designed prefab that's designed to be easily replicated on any sidewalk," he says. So the new San Francisco bathrooms are all the same: they use the basic footprint of JCDecaux's basic model which you've seen in a lot of cities, but have customized features designed by the architects at SmithGroup, including a distinctive dimply steel skin. Nion also "strongly believes in a self-cleaning mechanism," which in JCDecaux's new toilets includes a nifty seat-scrubbing machine that deploys after every use, a bacteria-zapping UV light, and a floor washing cycle. But JCDecaux also pays for maintenance crews, and has even hired attendants at some toilets — and again, this is all included in the contract with the city.

Instead of continuing its deal with JCDecaux, LA opted to launch its own in-house public toilet program, buying off-the-shelf prefab bathrooms and contracting its own maintenance crews. Which is fine in theory, but it hasn't resulted in a boom of more public bathrooms. One reason LA hasn't built more places to pee is because installing public toilets in the public right-of-way using public agencies can be prohibitively expensive. Just last month, San Francisco threw a huge potty-themed party, complete with poop emoji cupcakes, for a public bathroom opening that was originally estimated to cost $1.7 million (this was a different type of bathroom, not one by JCDecaux). That estimate, while seemingly outrageous, is actually pretty close to what Nion sees on the ground in U.S. due to the way cities contract these projects. "What gets expensive is the utilities," he says; just the trenching can run $500,000. In San Francisco, after officials were lambasted for the $1.7 million price tag, the toilet ended up getting installed the same way Tokyo's did — a private company (in this case, a modular bathroom manufacturer) stepped in to front the cost, construction materials, and labor. It cost closer to $200,000.

LA should certainly try to install more public bathrooms in tourist-heavy sites in anticipation of 2028, but Nion says these kiosk-style toilets aren't really designed for high-volume use. The city will still probably need its streets lined with portable potties in 2028, he says, the same way we see them distributed to centralized hubs during CicLAvia events. Truly expanding bathroom access at scale might look more like what's happening in Hollywood, where Councilmember Hugo Soto-Martínez allocated city funding to renovate and open public bathrooms as part of a new visitor center in an empty Walk of Fame storefront. And even though a lot of our new transit stations don't have bathrooms — making long trips very difficult for transit-loving toddlers! — it's not too late for Metro to get serious about putting permanent public toilets on more of its properties.

But Nion has another idea. Most of the Perfect Days toilets are not sidewalk-situated, he points out, they're actually renovated park bathrooms, which he says makes a great case for improving and expanding the existing bathrooms managed by LA's Department of Recreation and Parks. The plumbing exists, the site work would be less invasive, and they're distributed somewhat equitably throughout the city; according to new Trust for Public Land ParkServe data out last week, our park bathroom ratio (1.4 per 10,000 people) is not totally abysmal. The experience could definitely use an upgrade: as a mom who has spent a lot of time in LA's park bathrooms, the vibe is less Wim Wenders, and more Saw II. This is not the fault of LA's hard-working park staff, of course, but of LA's city leaders who have opted to starve their public spaces of resources. So let's find some money elsewhere. Destination bathrooms at all LA's parks could be paid for by corporations — who's the Uniqlo of LA? — and would be the perfect legacy commitment from LA28, which is already funding youth sports programs in these same parks. In city with a busted budget that just tried to eliminate hundreds of Rec and Parks staff, the door is wide open for a Tokyo Toilet-style model through a brand-new public private partnership. Our very own pee-pee-pee. 🔥

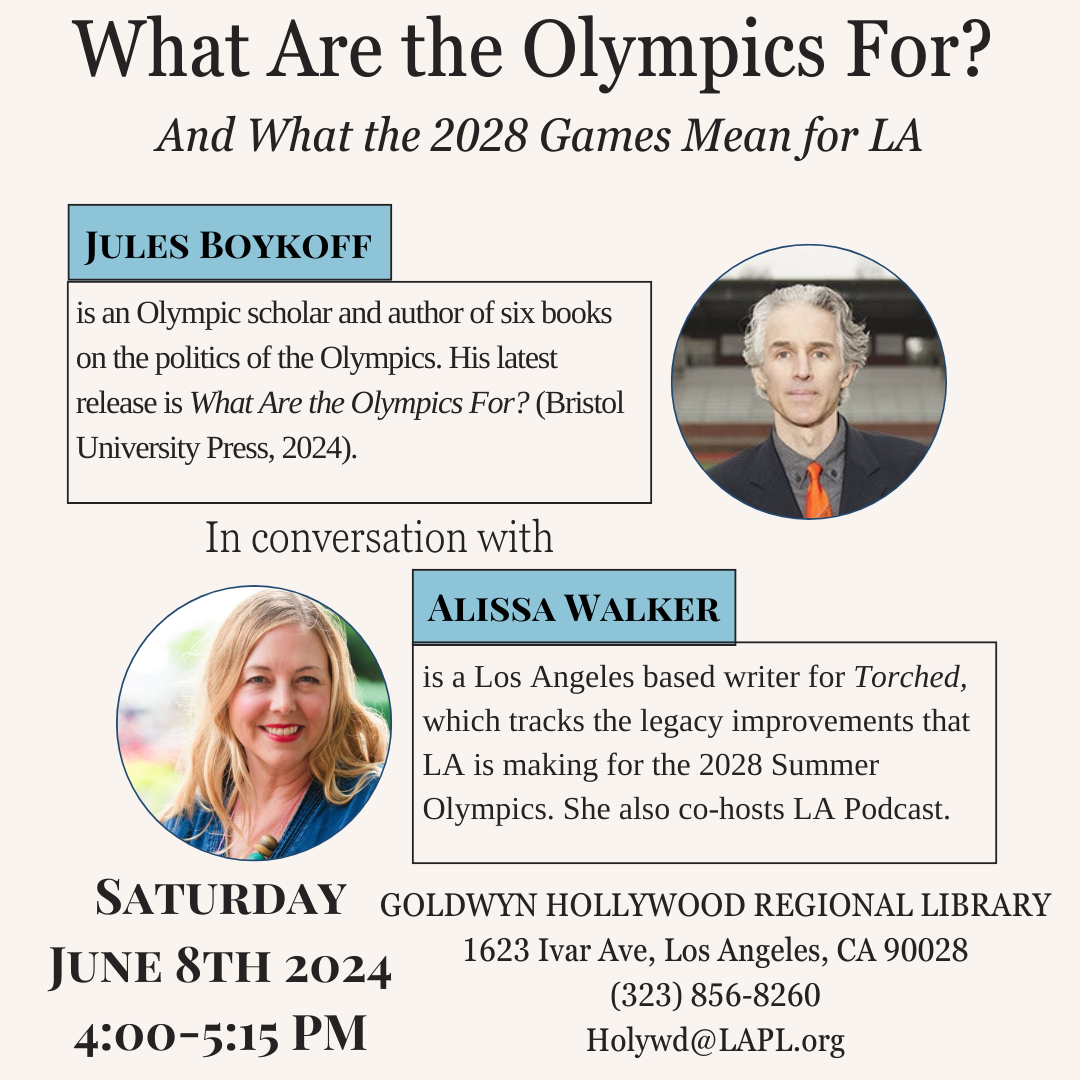

Speaking of excellent public facilities, I'm thrilled to announce the very first Torched event, hosted by the Goldwyn Hollywood Regional Library. Join me and Jules Boykoff on Saturday, June 8 for a discussion about his new book What Are the Olympics For? and what all of this means for LA. Here's a post about the event, and you can RSVP here (the date is being fixed, it's June 8!) or share the flyer on Instagram (this has the correct date!). This event is free and open to the public but future events will have limited capacity — consider leveling up to 🔥🔥 for early access to all Torched talks and tours. And see you there!