Torched Talks with LA Commons' Karen Mack

What's planned for arts and culture in 2028? Join us at Friday, May 23 at noon on Zoom

On a regular non-fire day in the Los Angeles area, your lungs have likely been compromised before you even step outside your home. That's because gas stoves, found in about 80 percent of all LA households, emit dangerous pollutants, and the research on how bad they are for you just gets worse and worse. Once you get outside, it's not much better. LA's air is consistently ranked as the dirtiest in the country, and it's even worse if you live near freeways, ports, airports, warehouses, or one of LA's many active oil extraction sites. That's a risk you are taking on a daily basis just by being an Angeleno — even before you throw in multiple major fires.

I say all this not to scare you but as a way to understand how bad the air situation was for all of us before the events of the past two weeks.

Reporting on fires turns you into an air quality freak — so much so that I started writing about both outdoor and indoor air. My interest in wildfire smoke in particular comes out of my own personal experience. My youngest was born amidst the region's worst back-to-back fire years, and during the Woolsey Fire he got a runny nose and a cough that lasted for months. When our doctor recommended ear tubes to prevent constant infections, the reality of the situation — that his health might have been impacted by a climate disaster — didn't hit me until after the surgery. I take this all extremely seriously, and you should too.

In 2018 I had bought masks to report on the Woolsey Fire, but it didn't occur to me that I'd need to wear them in my neighborhood. I certainly didn't think about how to protect my baby. There weren't these same conversations we're having now about the dangers of smoke and ash. We've come so far in the last six years thanks to increasingly insistent public health messaging. That's good: wildfire smoke is extraordinarily bad for you, and particularly bad for kids. And while the ash from a wood fire is never good to inhale, in structure fires, really nasty compounds, particularly from burning building materials, can glob on to the particles. (More on that in a minute.) Exposure to smoke and ash contribute to short-term illness and lifelong health problems, and the indirect death toll from these fires could end up being in the thousands. Everyone is correct to be vigilant.

At the same time, we're so bombarded with information during this highly charged moment that it can be hard to find the answers we need. And yes, some messaging blunders — like a water boil notice that was only meant for the Palisades but accidentally went to everyone in LA County — have certainly freaked people out. (Here are all the current water notices; yes, any rain could impact water quality, particularly at beaches, which officials are monitoring.)

As someone who writes and thinks about this all the time, I wanted to answer some questions I'm getting and talk about what steps I'm taking, not necessarily as a reporter, but as an LA mom trying to do the right thing.

First, a hearty welcome to all the new AQI obsessives! It's a big tent, and we're happy to have you — we even allow New Yorkers now. I probably don't have to tell you what the Air Quality Index is, but here's an excellent explainer; most weather apps now have it integrated so you can check it as easily as the temperature. I've been using fire.airnow.gov because it also shows fire conditions, but if you feel like you're not getting a localized-enough picture of air quality from your AQI app, use LAUSD's Know Your Air, a high-quality sensor network, to find the nearest LAUSD school near you.

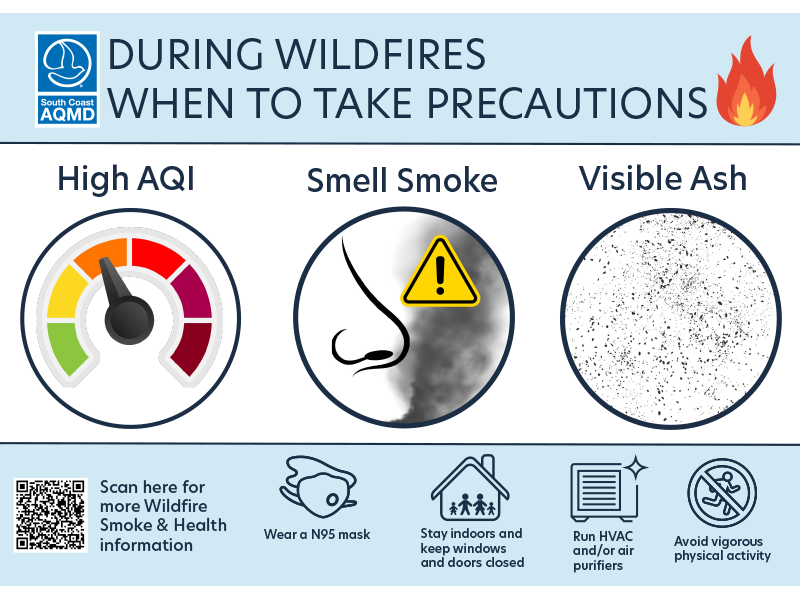

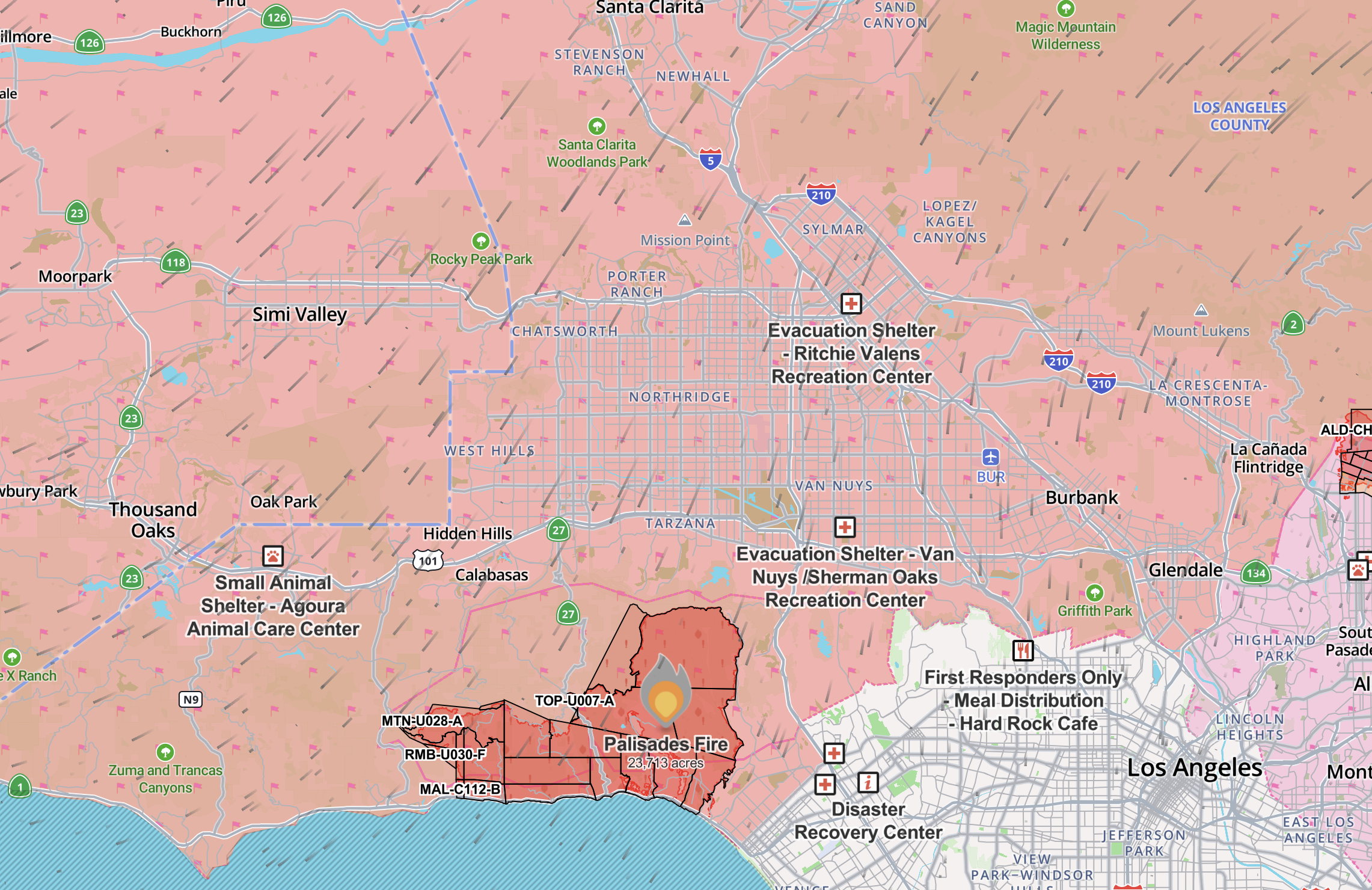

AQI measures a range of pollutants, including particulates like PM2.5, the tiny particles that are most dangerous to breathe. Most of the time it's a very reliable way to determine if it's safe to be outside. But during and after fires, AQI doesn't always tell the whole story because ash particles are usually too large to be detected by the sensors. So you have to add two more factors to your analysis. South Coast Air Quality Management District, which a lot of people just call AQMD, is LA's regional air-quality administrator, and their messaging explains it very well: If the AQI is green or yellow, and you want to be sure it's safe to be outside, you can use that information as you confirm weather conditions with your own nose — does it smell like something's burning? — and your own eyes — is there airborne ash flitting around?

To repeat: this doesn't mean AQI is not a reliable indicator, it's just one indicator to use during these events. And it's a pretty good one overall.

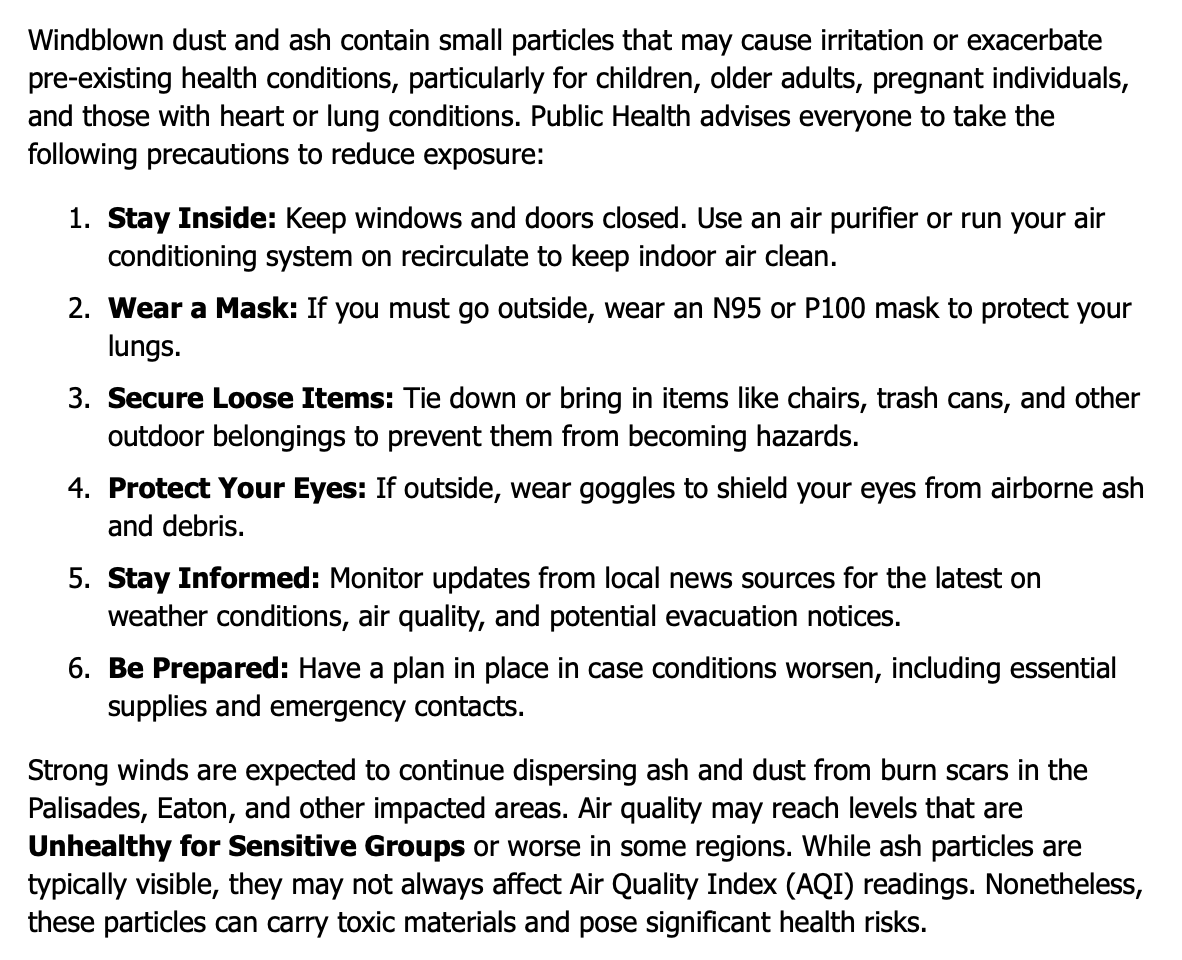

But what about the really nasty compounds I mentioned before? The good news is that LA County public health officials not only issue warnings about smoke, they also issue different warnings to protect us from blowing ash and dust that might contain those other potentially toxic materials. Here's the public health guidance delivered at the January 14 press conference. We are currently under a windblown ash and dust advisory that expires tonight, January 21, because one dangerous wind event can make the air very bad all over again.

This is what our public health officials are recommending we do to protect ourselves during a windblown ash and dust advisory:

Yesterday was the perfect illustration of how you can't rely on AQI alone. It was a sunny day, the AQI was green and yellow, and it didn't seem windy at our house; we made a park outing. But when we got there, I noticed there were huge clouds of dust ripping through the park. This guidance was exactly right. The park was way too windy anyway. We packed up and went home.

There are other factors to consider. A big one is your distance from burn areas. It's difficult to say a certain distance guarantees clean air due to changing weather conditions. That's why fire.airnow.gov is so great; you can see the perimeters clearly outlined and even read the "smoke outlook" — here's the one for the Palisades Fire — which has specific information for each fire burning. Wind conditions also vary so widely in our microclimate-dotted region. Watch Duty has a nifty wind-tracking feature where you can easily see if you're downwind of a burn area. Just like we all got to experience during the evacuation process, you have to make an informed decision about your own actions.

One thing you don't need to do is spend your evenings Googling a new chemical compound you just learned the AQI doesn't monitor. The health risks from smoke and ash are bad enough on their own to simply avoid them. Just do your best during this time to protect yourself from the smoke and ash and you will protect yourself from other potentially toxic materials.

That being said, there are two groups of Angelenos who will have to take extra precautions:

One trick I've learned from reporting on these topics over all these years is asking experts what they, personally, are doing to protect themselves from bad air. So I found two scientists who actually live here and have written up immensely helpful, highly personalized answers to all these questions.

For the eastsiders, I have "Hazards of smoke and tips for cleaning after fires," by Paul Wennberg, a professor of atmospheric chemistry and environmental science at Caltech, who lives in Pasadena: "When the air quality is good, I do not wear a mask outdoors and keep the windows in my home open to help remove the smoke (as long as the smell is worse inside than outside)."

For the westsiders, I have "Ash below, blue sky above: Is the air safe?" by Suzanne Paulson, UCLA's Center for Clean Air director, who lives on the Brentwood/Santa Monica border: "When the sensors are green and there is no obvious ash floating around, there is no reason to curtail activity now! I rode my bike to work on Wednesday, January 15. The air was much cleaner than average for my area."

Now I'm sure you've seen conflicting information from LA's real air-quality experts: Instagram influencers, vibes-based Substackers, and people forwarding emails from their mom's neighbor's friend's trainer. Some of this inaccurate information is being improperly attributed to a Coalition for Clean Air webinar "The Fires: Air Quality, Public Health & What to Do Next," attended by over 8,000 people on January 15. I contacted the Coalition for Clean Air and they are aware of the problem. They pointed me towards this document of the questions answered during the webinar, which I highly recommend, mostly because the webinar is very long. If you'd like another source, I recommend KCRW's "Wildfire Public Health Information Panel for Families," which is a shorter and less technical version of the same information with a lightly edited transcript on the same page. Another expert I've been listening to every day is UCLA climate scientist Daniel Swain, who has been the best resource, hands-down, on these fires. He discussed all the air-quality rumors as part of a livestream last week.

Like pandemic-era guidance, air-quality guidance is just that: guidance. It's information for you to use in order to assess your own risk. Clout-posters saying "don't trust the AQI" or "public health officials aren't telling the truth" takes us down a dangerous path, especially at this moment, when, for all we know, Trump 2.0 might very well stop reporting key public health indicators. Being able to look critically at localized data, seek out information from trusted expert sources, and listen to what LA's health officials are actually telling you is now more important than ever.

Finally, since many of you have asked, here's what I'm doing.

We are in Historic Filipinotown, far away from a fire, but we were directly under the Eaton Fire plume. Ash fell like flurries at our house for days — I mean, an entire burned magazine page landed in my yard — and it's still stuck to some of our plants over a week later. I didn't see any evidence that ash had blown into our home, but I still wiped down all the areas around windows and doors. It reminded me a lot of scouring my home for potential lead exposure when my oldest had elevated lead levels from the paint in our old house.

We have the purifier recommended here in my kids' room. We've been running it on high 24/7 since January 7. I change the filters every six months, and it just happened to be around this time, but you may want to change it more frequently this year. (You can also make your own.) Their bedroom is the "clean room" in our house. We also have a MERV 11 filter on our HVAC system, but I plan to upgrade to MERV 13 when I switch it out. As I wrote last week, one of the reasons I felt comfortable taking my kids to school on the really bad smoke day is because LAUSD campuses have new air filtration systems that are better than the ones in our own house. After some blunders on that first day, I think LAUSD's decisions to reopen schools and resume outdoor activity have been spot-on with the science. The district also just sent parents a message that they're still monitoring conditions and will switch to indoor activities if needed.

When the AQI is bad I watch for green and yellow windows to plan outings. (I do this all the time, by the way, not just during wildfires.) One day that first week when the air was not great but my kids really needed to get out of the house, I waited for the AQI to dip below 100 and we went for a short walk in masks then rode the bus home — our public transit fleets also have great air filtration after the pandemic. Last Friday night, when the AQI was green and there were no windblown ash and dust warnings, we dined outdoors — restaurants really need your support! — and we haven't worn masks when it's green or yellow since, although when it's windy we've limited our time outside.

Am I personally worried? I am worried about the particulate matter that blankets the LA basin every single day. I'm worried about hosting a megaevent during LA's smoggiest months. The environmental disasters parked in our own driveways, whether they caught fire or not, still pose the gravest threat to our health. And for LA County families that live near the port, or distribution centers, or oil wells, or battery recycling plants, chronic respiratory illness and elevated cancer cases from many of the toxic compounds that people are suddenly so concerned about are not a hypothetical risk but a daily reality.

If everyone anxious about LA's bad air now could throw that energy behind the advocates who are working to stop electing representatives propped up by fossil fuels, pass policies that help Angelenos drive less, and obliterate the petroleum industry, then we'd all breathe easier.

But the #1 question people had for me was this: When will this end? And the answer is... never? Climate adaptation also includes adapting our personal behavior. Just like we all learned to religiously track AQI a few years ago, now we have to employ new tools to keep our families safe day to day. Obviously, when a new fire starts, the air quality will quickly deteriorate all over again. Until then, you have to do what's best for your physical and mental health. Many people I've talked to still won't resume outdoor activities until rainfall settles the ash and dust, and you know what? That also seems completely reasonable. We may get some rain as soon as this weekend. 🔥