The Grand scheme

This is the downtown that Frank Gehry wanted. When will LA's leaders give it to us?

"If your city has politicians telling you that the only way they're going to fix your transit system is by throwing a party for people from around the world, you go get yourself a better politician"

On a different timeline, the Summer Olympics would be wrapping up this weekend along the Charles River, not the Seine. For a brief moment one decade ago, Boston was the most well-positioned city to become the host of the 2024 Olympic & Paralympic games — until a group of Bostonians successfully organized to block the bid in 2015. The move forced the U.S. Olympic Committee to make a quick pivot to reliable permahost Los Angeles, who just happened to have a winning bid all ready to go. You know what came next. "We dodged a bullet," Chris Dempsey, a leader of the No Boston Olympics campaign, said last month. “We might have even dodged a meteor."

Earlier this summer I spoke with Dempsey, a transportation consultant, partner at Speck Dempsey, and co-author, with Andrew Zimbalist, of the book No Boston Olympics: How and Why Smart Cities Are Passing on the Torch. We could have talked for hours just about transit policy in each of our cities, but I edited our conversation down to to a few key themes: why organizers knew the bid was bad for Boston, how they took on some of the most powerful people in the city, and what LA should keep in mind leading up to 2028.

Torched: When did you start to realize, as organizers, that this was not going to be a good deal for Boston?

Chris Dempsey: We had concerns very early on. The reporting started very quietly in 2013, in the midst of a mayoral election, which was the first open-seat mayoral race in 25 years in Boston, because we had Mayor Tom Menino since the early '90s, and he decided not to run for re-election. And so, all of a sudden, it was a free-for-all. There was enough reporting in the Globe, in the Herald, and elsewhere, to understand that it was a very powerful set of people who were pushing the bid, and that, frankly, certain mayoral candidates might be more inclined to support such an event than others. There were 13 people running that year, and the person who won was the person who was most likely to support an Olympic bid of the 13.

After that election, a bunch of us were bummed out that we were not helping our chosen mayor move into office and get settled in. But we knew this bid could be the next big thing in Massachusetts government. And in the area that I cared about, transportation policy, where I’ve spent most of my career, it felt like if the bid went forward, it would be the dominant story for the next decade. I had read enough about the history of the Olympics in other cities. I'd seen the images of the abandoned stadiums and read about cost overruns in places like Greece and Russia, but also in London. And I knew there were going to be potentially enormous drawbacks, both in real, hard-dollar costs, and in opportunity costs.

And it was a powerful group of people pushing it.

Boston was, in a lot of ways, the perfect city for hosting the Olympics. It's large enough to have the scale to have the financial resources to get it done. But small enough that there are a handful of people that if they get together and decide to do something, they can really make it happen. I think we're a great sports town. Boston is a city that looks really good on television. And we're on the East Coast time zone, which is the most valuable time zone in the world. The events that happen during the day in Boston are primetime in Western Europe. Something like 40 percent of all television watchers are on the East Coast time zone in the U.S. And then even the events that go late night in Boston are still primetime on the West Coast. And then the institutions of Harvard and MIT and the other universities here; we knew that the IOC would want to be associated with them. So all of that was a really compelling package. And it was a strong group of people.

But the other thing that we saw was that there was no obvious opponent that normally would step up to question a big project like this. The ones that normally would were conflicted out. One of the entities that would normally raise questions was the Boston Municipal Research Bureau, which is kind of like a fiscal watchdog for the city that issues reports saying, wait, hold on a minute, this is not the right thing to do, there are real risks here. The leader of the bid was a board member, and a very powerful board member, so they're not going to put out a report against it. They're smart enough that they know where their funding comes from. So it was going to have to be a grassroots effort.

And if I'm remembering right, in the global Olympics lineup at the time, we already had London. And then right after that, we had Rio.

Right. London 2012. Rio 2016. Tokyo 2020.

And London, while very quote-unquote successful, also unearthed other problems and Boston could probably take a lot of lessons from that.

Very much so. London's bid went something like two to three times over budget. And what they would say was, in fact, they were under budget, but they're only under their revised budget. They did crazy things in London. They promised no white elephants very early on. And it led them to make some interesting decisions, for example, it cost them more to retrofit the Olympic Stadium into a soccer stadium than it would have cost to bulldoze the Olympic Stadium and build a whole new one. But that would have been embarrassing, that would have been admitting that they had created a white elephant. And so to uphold the legacy they needed to spend more money to retrofit the one that they had built. Some might call that successful. I would not call that successful.

The other, I think, really important dynamic in the United States, and this is true in California — although maybe to a lesser extent, because of the size of the California economy — but in the UK, the Olympics are essentially funded by the national government. So there were 60 million people that live in the UK, and they would spread the $10 billion or so cost across those 60 million people. It’s not great, but it's not a lot of money per person. We would have been spreading it over 6 million people in Massachusetts. And we've got a nice strong economy, and we’ve got a high per-capita income relative to other states, but not that many people. So that was a big reason why.

When did you start to see that you might be making some headway with this message?

So over the course of 2014, we built our credibility with the press. And I would describe it as a thorn in the side of the Olympic boosters. Our whole strategy here was mostly to take advantage of the fact that Boston 2024 boosters would have to be putting out press releases and talking about all the great things that would happen. And if we were credible enough, good reporters in their newsroom would turn to us to tell the other side of the story. They would get a quote from up there, and with very few resources, we could match, almost word-for-word, the megaphone that the pro side had. And you could tell early on that that was frustrating. There was a certain point in 2014, where a reporter got the bid leader on the phone, and he said something like, what have these people ever done for the city? And that was not a wise thing for him to say.

Oh, I don't know, you’re only, like, fixing the transportation system that hundreds of thousands of people in your city use every day?

Right, but I was not at his level, this powerful person in Boston. And frankly, on the night of the USOC election, we thought the bid was going to lose. [In 2019 it was changed to USOPC: U.S. Olympic & Paralympic Committee. — AW] We all thought they’d go to LA. We thought there was maybe a 20 percent chance they were going to choose Boston. Then in January, overnight, the Olympics went from an impossibility to an inevitability. We went from why would they come here? to oh my god, they're coming here. And all of a sudden, it was the top news story in the region pretty consistently for the next six or seven months. And that's where we reached a new level as an organization in terms of getting organized and holding public meetings. It became basically a full-time job for me, and for one of my colleagues.

So, coming back here, LA's devastated at this point. Obviously, we think we're the shoo-in, we had been working so hard to get this thing, and it goes to Boston. I was looking back at some stories at the time, and there were comparisons between the cities. I remember people were worried about the historic brick sidewalks. Boston is a tourist town, but unlike LA there were real concerns about a bunch of people coming to the city.

If you look at our hotel occupancy rates in the summer they are well over 95 percent. We are jammed in the summer, we are packed with tourists. We are very comfortable hosting the world. One of the great moments every year in Massachusetts is Patriots Day where we host the Boston Marathon, and people from around the world come to run in our streets and celebrate that event. Another great moment is September, every year, when our universities open up, and people from around the world come to study in the classrooms of our universities. But the Olympics would bring in a new level of scrutiny. And frankly, that was always the best argument that Boston 2024 had, that this was going to force our city to make some changes. Company’s coming over, so we’ve got to clean things up.

Deferred maintenance for transportation was a big one.

Yes. And while deadlines are helpful for getting things done, they can also be extremely harmful. They can significantly drive up the cost of capital projects when you have an artificial deadline. Let's say you decide you're going to renovate your kitchen for your daughter's graduation party. And your contractor knows when the graduation date is. And they say, we need another $10 million to make sure that kitchen gets done on time and you're like, well, gee, I’ve got this party for my daughter…

Oh, this sounds exactly like what could happen with our convention center.

But then there was also the issue of the lack of transparency by Boston 2024, which was promising all of these amazing things, but then unwilling to share the details. There was basic distrust there. They were refusing to share documents.

You’re saying the actual bidding documents?

Yes, they would be glad to go on TV and talk about all the wonderful things that they were going to do. They were unwilling to share the documents that they had submitted to the USOC.

Why?

Because they lied. And I'm not exaggerating here. They told the USOC that certain rail lines were planned and funded. You know, Bostonians are a pretty savvy bunch. And we like to make our own independent decisions on things. We like to have the data ourselves. Not having that was undermining all the bid’s credibility.

And then there was a second thing that dramatically accelerated the timeline for this process. We had the most snow in recorded history in the winter of 2015, really starting in January, and then in February, it just dumped on us. Feet and feet and feet of snow. And the MBTA for the first time in my lifetime — I was like 31, or 32, at the time — actually shut down for multiple days.

That had never happened before for many people.

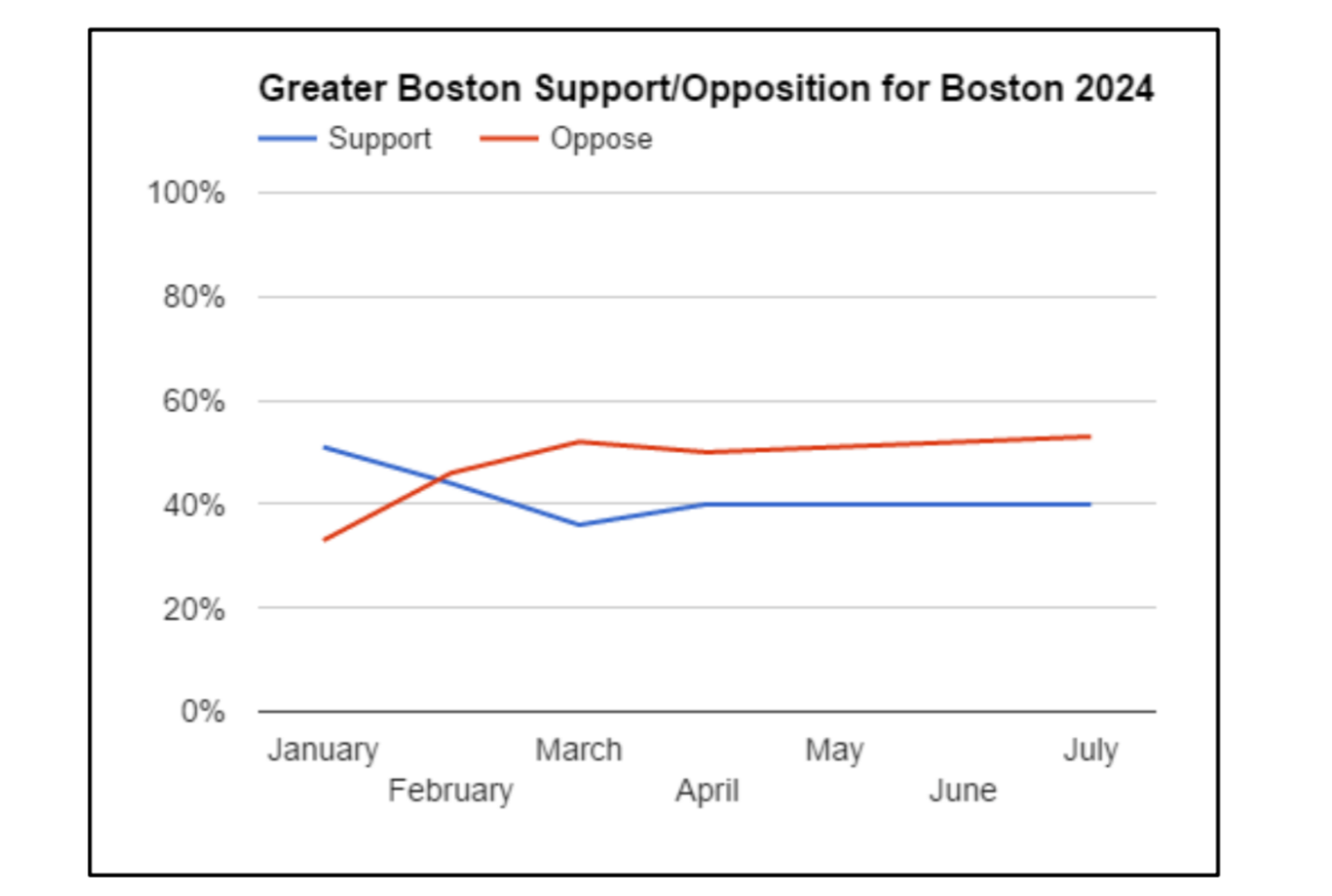

Right. And people started to say, okay, we can't even get our own people to work with our transit system. And now we're inviting the world to ride our transit system? Where are our priorities? And do we really want to start to prioritize the needs of this event over the things that we need to get done on a daily basis, which again, was totally consistent with our message. And if you look at the polling, Boston 2024 started with majority support in January after the USOC decision. By March those numbers had basically flipped and they never really recovered. Their positivity got maybe into the low 40s a couple of months later when the weather got better, but they were never what you would call above water.

Even the fact that there was polling, I think that’s another important comparison to make. Every time there's polling done here the news coverage always says, well, the polling shows support, but then you look a little bit closer and the questions are always a bit leading, like do you think they’ll be good for LA, not do you want them?

Andrew Zimbalist and I wrote a book about our experience, and we dedicated that book to two groups of people. The first was to the people of Massachusetts, being the savvy people that we thought they were going to be. And the second was to the media, because we would not have succeeded without an engaged and interested and curious media. And that includes the pollsters.

So the polling group that was working on this was called the MassINC Polling Group. They realized that this was an interesting topic. At first it was going to be every three or four months, then I think it became a monthly poll. That was really driving this story. And if we had not had that, I think it would have been really hard to make the case that we were on the side of the majority. Even when the first poll came out, and our side was 32 percent, we still felt like that was a 32 percent worth representing. But once we swung to the majority — and we're like the scrappy underdog, we spent less than $10,000 — we knew we had the people on our side. It was a really helpful and effective narrative for us that people were very willing to rally around.

So this is now 2015. And you start to see almost a threat from the boosterism pushback, they’re desperate to spin it like, oh, if we don't do this, then we'll never get anything done.

Well, some of those boosters are still saying we would have fixed the MBTA.

And there have been huge problems with Boston’s transit over the last few years, a whole bunch of shutdowns, and I’m sure they bring that up.

Right, and we would all be riding unicorns and flying in magic carpets if we just had the Olympics. If your city has politicians telling you that the only way they're going to fix your transit system is by throwing a party for people from around the world, you go get yourself a better politician.

And it's something you have to think about when you’re electing people! Like we still have two local election cycles before the games. We may even have a different mayor.

Our current mayor, as a Boston city councilor, was the first elected official in the city of Boston to raise some tough questions. She did an WGBH op-ed that she wrote, which took a lot of guts. I will always be grateful to her for doing that.

So you had some electeds raising doubts. Tell me about the mechanism of getting it booted in those final days.

This is where it ties very closely to LA. I always thought about LA like a spurned lover that was always waiting in the corner.

Oh, hello there… I knew you’d be back.

Ready to be welcomed back with opened arms. So it became pretty clear over the course of the summer after that tough winter, that these poll numbers were not rebounding. And Boston 2024 had one more chance to get it right. They changed the leadership of the bid. They created something they called Bid 2.0. And this was the chance to sort of wipe the slate clean, start fresh, and develop a plan that was going to meet the needs of the USOC and meet the needs of the public.

And I'm going to just go on a quick tangent here, but we call that the “boosters’ dilemma.” You're pulled in two different directions. On the one hand, you're telling the public: don't worry, this is going to be low-cost, it's not going to be disruptive. On the other hand, you're telling the IOC you'll build them the best stadium they've ever seen. Money is no object, because we care about hosting, we don't care about financial responsibility, we want you to be treated and wined and dined. And we want your television sponsors to be happy. And you can't do both things at once. So then 2.0 comes out, and it's meant to be the answer to all of these problems with questions we've been raising, and it falls forward. They still didn't have locations for certain venues. You're telling us it's not going to cost any money, and you can't even identify where the venues are.

They didn't have a public venue plan?

They had that in their bid to the USOC. But they did not have it for Bid 2.0. Because, you know, again, the boosters’ dilemma here, they had places that they knew they wanted to have venues, but there was no venue there. They just could not identify enough pragmatic, realistic venues. Then the second thing was they talked from day one about cost overrun insurance, that they were going to get insurance that was going to protect taxpayers. Okay, cost overrun insurance for an Olympics does not exist, it is not a sellable insurance product. They could not identify the insurance. There was no way to turn around public opinion.

The next poll comes out after Bid 2.0. and the polling numbers are basically unchanged. They're basically below 40 percent support. Remember, by that point, Boston 2024 had promised a referendum, they promised a statewide vote, and it became clear that there was a real risk that that referendum would fail and the USOC would have no American city to enter into the 2024 summit. And the USOC obviously needs a U.S. bid for its sponsors or else they don’t make any money. So I think the USOC was in communication with LA and said, hey, if this Boston thing doesn't go well, and they pull out, you’ve got to be there to save it. And of course, LA said yes. There was a board meeting in late July to make the decision. I don't have any physical evidence of this, but in my view, they knew full well that they were going to LA instead. They had made that arrangement already.

And then just from this side, it wasn’t until 2017 that it was official, but it was basically a done deal. Because over the course of the next year-and-a-half, two years, it became very clear nobody wanted it.

And we were part of that, too. We had outreach from the people in Rome, who were the grassroots opponents there. And then they elected Virginia Raggi, the new mayor of Rome, who came from a kind of an independent political party, and she shut down the bid in Rome. In Budapest, they had a grassroots group of university students who collected signatures to force a ballot referendum on the issue, very much embarrassing the president and the mayor. It became clear that it was not going to pass. And so they pulled their bid. We had a couple of Skype calls with them. They were inspiring to me as young people who were like, we know we live in a country where democracy is declining, and we're going to do something about it, and this is our avenue to do so. And then Hamburg, Germany — which is very similar to Boston in a lot of ways, a northern port city that reinvented itself as a university education town — they flew us out for a conference in maybe September of 2015. And in late November of 2015, the city of Hamburg voted, and they voted it down.

That was great vindication. It showed that a sophisticated and smart city should be asking tough choices, and should not take it as an obvious yes, the Olympics will be good. And I do understand the political context of LA is very, very different. I went to Pomona College in Claremont. People talk a lot about the Olympics with a lot of excitement.

But I would argue it was hard to get too excited this time, because as this was happening, Trump gets elected. And then we had to play nice with his administration in order to get the games and it was so maddening and gross to watch these local officials pandering.

Like watching Eric Garcetti getting down on his hands and knees going into the White House? Mr. President, I know we disagree on some things but we can agree on how great you are, and how great the Olympics are...

...and, by the way, we need that federal funding for that train line. I mean, that was really rough, and then it was like that for years! And there could be a continuation of that. I think also for some people it felt like such a victory but with an asterisk because it was this double award and we had to go second after Paris.

Well, that was a reminder that the IOC is making up its own rules. But you do see these things happen in cycles. LA knows that better than anybody. For the ‘84 games, the IOC was in another moment, like they were in 2017, where there's only two bidders that show up. Then it was Los Angeles and Tehran, and Iran was on the verge of the Iranian Revolution. So they dropped out, and all of a sudden, LA is the only bidder. The IOC wants to have as many cities competing against each other because they get to extract value out of a city. When you show up to an auction, and you're the only bidder, and you know that the auctioneer has to auction the item, you get a very, very good break.

I think we could have negotiated for a lot more. So much more. But I will say that there still is a lot of negotiation happening outside of the city of LA. Some cities like Santa Monica still haven't signed their games agreements. You have LA County saying it wants to do a community benefits agreement. There is some pushing back even at this late stage.

In my view, the lessons that people should take away from the ‘84 Games are not that LA is inherently better at hosting the Olympics. It’s that LA had leverage in 1984. I don't think it's smart for cities to bid on the Olympics, but if they're going to, it should only be in extreme circumstances where they have all the leverage. I think LA had some leverage in 2017 — but not as much as they had for 1984. 🔥