The Grand scheme

This is the downtown that Frank Gehry wanted. When will LA's leaders give it to us?

Talking to UCLA's Juan Matute about this year's Lake Arrowhead Symposium and how LA can leverage megaevents to create lasting public benefits

One of my very favorite people to talk to about how to make Los Angeles better is Juan Matute, deputy director of UCLA’s Institute of Transportation Studies. Here's us way back in 2019 talking about how to improve public transit — all of which still holds up five years later. Listen just to hear how quickly he spits out bus ridership stats on the Vermont corridor!

More recently I spoke with Matute for my Dwell story on how LA can pull off a car-free games, where I mentioned that he's coordinating this year's UCLA Lake Arrowhead Symposium Mega Events: Major Opportunities. For three days in October, attendees will hear from an impressive roster of speakers — I'll be there, too, and you can use the code TORCHED to get $200 off regular registration tickets — with the goal of "developing concrete plans for leveraging these megaevents to create lasting public benefits." Since these are the very same topics we’re interested in here at Torched, I thought it would be illuminating to peek inside the plans for the symposium one month out. I talked to Matute about LA’s regional planning vacuum, the promise of "Olympic lanes," the importance of gathering places, and the one megaevent-related topic that’s not getting nearly enough attention.

Torched: I don’t know about you, but it’s been disappointing tracking the actual physical legacy of the last two games. All you have left of 1984 in Expo Park are these hundred or so crumbling benches.

Juan Matute: Which I think is the case with a lot of legacy projects. Los Angeles embraces the new. It kind of forgets the old. Some of the old gets landmarked or sponsored by corporate interests or civic arts interests, and is preserved, and some of the old just kind of withers away. And you can really tell what people are interested in by what they allow to wither away. And so benches in parks and other places have withered away.

Like, at least it's a bench, but we can do so much better than a bench this time around.

It's a bench, so it meets the IOC’s expanded requirements for legacy, which is that there's going to be some sort of Olympics-related association or branding, and that it's relatively permanent and low-maintenance. I guess the benches are benevolent rather than malevolent. So it's a step in the right direction, but it's literally the least they could do.

But this time around, have we taken "no-build" so literally that there may once again not be some kind of physical legacy?

This legacy plan from the previous mayoral administration is called 28 by 28, which was to finish 28 transportation projects in time for the 28 games. That could have been a rallying cry. Instead, you have the marquee project, which is this Westside subway extension, and the previous councilmember from that district not letting it do after-hours or overnight construction because he’s upset with the agency and didn't want to allow them to relocate utilities on his watch.

That's the story of LA that I know, which is that you may have this overarching goal, and then everybody kind of picks it apart until they're getting everything they want out of it. And then there's nothing left that's overarching.

And a lot of well-named plans with very little follow-through. Like 28 by 28? Just brilliant, excellent branding. But then we never had the annual check in to see if we had the money to allocate to it.

We never had the 22 by 22 interim. It was either 28 by-the-time-I'm-gone-as-mayor, or bust. And everybody chose bust.

Talking about overarching goals for the games, what seems most glaring at the moment is that LA is lacking any type of regional vision.

We have 191 cities in the Southern California Association of Governments region, 88 in Los Angeles County, and they're still kind of in competition mode. They're still competing for either hosting events or not hosting events. Sometimes they're competing with cities within Southern California. Some of them are competing with cities in the Midwest. It's still kind of seen as a zero-sum game, where, if some city gets ahead, other cities fall behind. Rather than, let's figure out how to create an opportunity to help out Southern California and all cities as a result of this pretty impressive global event.

This seems like a really good opportunity to actually come out of this with something better.

I think one of the challenges in LA and Southern California is the fragmentation among the government entities. SCAG tries to do some level of coordination, but they're very limited in what they can do. They're primarily focused on regional transportation planning. So at this symposium, we're going to be exploring the need for civic-sector planning and policy institutions that are thinking regionally. It's one of those things you don't notice the absence of in LA until you look at the presence of something like this in another region.

Talk about a few of those good models.

The New York metropolitan area has the Regional Plan Association. That’s a very fragmented region across three different states with three different governors and different bureaus wielding power. The Regional Plan Association comes together, and they'll develop ideas based on data and information. They'll circulate them, they'll develop constituencies for them. They'll do all of the things that it's actually kind of hard for governments to do, because if the idea is not baked — and by nature, some of these ideas are not going to be baked — people shoot it down very quickly when it enters the government arena. And so these regional organizations can think about baking ideas.

Like congestion pricing, for example.

In New York, they advanced and developed a constituency for the Manhattan congestion pricing scheme that was ultimately delayed permanently by one of those governors. But that proposal would have never been incubated by a single agency; that takes some sort of civic sector institution. In San Francisco, it’s called SPUR, San Francisco Planning and Urban Research. They have branches in San Francisco, Oakland, and San Jose, and they think everywhere from local to regional. And that's really important, because so many of California's policy areas are local conflicting with regional. At the Arrowhead symposium we're going to have the CEO of each organization.

These are really good models. And it's not to say that the agencies aren't coordinating like this here. But Metro is doing the majority, if not nearly all, of the legacy transportation planning. And while Metro runs a lot of systems and networks, they often don't own the land or control how people get to their stations. And four years out, I feel less and less confident anything else will change.

It’s seen as a political loss in Los Angeles whenever you say, hey, we're going to prioritize people instead of cars. If more politicians were willing to invest on the prioritizing-people side of that tradeoff, within their cities and council districts, then we would have a lot of opportunity to do quick-build, which is accomplishing like 99 percent of the transportation benefits, especially in a medium-volume or low-volume corridor, at probably 5 to 10 percent of the cost.

You’re reminding me of something said by Councilmember Traci Park, who chairs the Olympic committee for the council. She told the Los Angeles Times that she would like to see a bike lane network between Olympics venues for 2028. But she also says that HLA, this ballot measure we passed to force the city to implement its mobility plan, has spending requirements that are prohibiting her from putting those in place. She sees the mandate from the voters to implement the city's long-term plan for bus and bike lanes as conflicting with the short-term goal of putting in temporary venue-to-venue bike lanes.

Measure HLA focuses on the bike-enhanced network and bike lanes where they were determined to be most needed based on how people live their lives and based on where traffic collisions occur. With the exception of a couple weeks in July and August of 2028 most people in Los Angeles don't like to go between sports venues; that's not a normal trip for people. And so while it might be great during the games to have, I don’t know, like a pedicab going between like two events in a nice, dedicated lane —

Oh those are so nice, I see them all the time at CicLAvia.

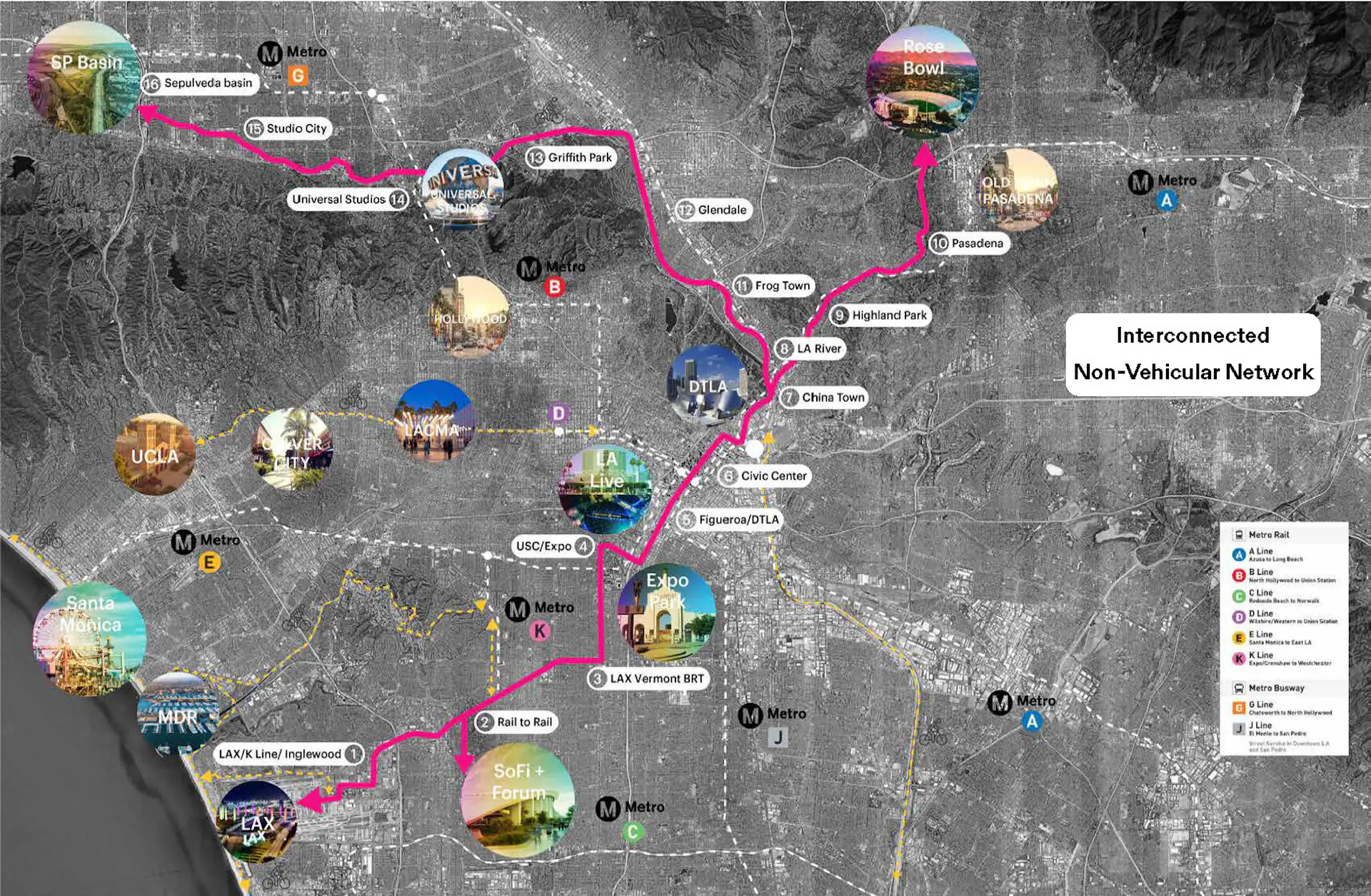

— HLA doesn't say that's a priority. But the challenge to implementing HLA is not funding. California spends $33 billion a year on transportation. A lot of it goes to roadway maintenance, expansion, operations, and very little of it actually goes to bike lanes and active transportation. And so if you shift a little bit more, you can double the money available to bike lanes and active transportation, and you can have it all. You can do the HLA network and you can do the network between venues. At the symposium, we'll be featuring an architect, Chris Torres, of Agency Artifact, who has this Festival Trail concept activating these corridors between venues, between neighborhoods, and between long-range bike projects, with arts and cultural activations, making it fun and exciting to go through an area, like a linear festival. We’ll be talking about that alongside some of these legacies, like bus lanes, and maybe even the on-highway network becoming an opportunity.

Talk about that a little. These would be the "Olympic lanes" on major freeways.

LA has really good transit bones in terms of how LA was built — along a light-rail network, the Pacific Electric Red Car. We have several maps of it up in the office here. It’s important to think of LA as a sprawling East Coast city oriented around transit that had an early version of Houston placed over it. We have this great legacy infrastructure from LA's first period of transportation and land-use. And because of that structure, we have really good on-street bus networks that can work really well. We have a grid. We have concentrations of neighborhoods. If we can take this IOC-mandated network of uncongested roadways that allows media and athletes and other high-ranking officials from host countries to get to events without being in LA's deservedly notorious traffic congestion, and we use that at other times beyond those two weeks for somebody who's commuting from North Long Beach to a healthcare job in Santa Monica. And it’s relatively inexpensive to do, it requires just a reallocation of roadway space. We can make this legacy where somebody has a much more fulfilling life because they're spending maybe 45 minutes to an hour going to and from work, rather than an hour-and-a-half each way.

But it all comes down to that messaging, and that begins today. As we’ve talked about before, in 1984, many of these elements that made the transportation of the games so successful were these voluntary commitments that were made, this appealing to the goodwill of the people of Los Angeles as part of their civic duty. And you don't think that can happen this time around.

‘84 was a different time in American history. Los Angeles boomed as a defense-oriented city that then further specialized in aerospace, electronic systems, and space systems. There's still a legacy of this around Los Angeles: there are different plants, and even different Superfund sites out past the San Fernando Valley. But Los Angeles was very actively involved in the Cold War. It was something that was top of mind for a lot of people who lived and worked here. The whole messaging around LA '84 was in response to Moscow ‘80, which was boycotted and not seen as an open games. Where, essentially, Los Angeles wanted to prove that one system of political, economic, and social governance was superior. That was a huge motivator. When you study the Cold War period in America, it’s having an enemy out there and saying, we would like to do things in order to defeat that enemy to bring people together. LA '84 brought in the sponsorships and made the profit, in part, because there was this global culture war happening. And if you're going to have a culture war, it seems like near Hollywood is a pretty good place to launch your salvos from.

And the boycott of our Olympics was one reason that the games were also smaller. I want to talk about one of your other topic buckets: public space and gathering places, something I feel like where we again fail as a city or region. What are you hoping to highlight as a way of creating these civic commons?

LA is a global city, and global cities are great for hosting the Olympic games, because you'll have significant portions of populations that have a family legacy — either because of direct immigration or second generation — from over 100 of the countries. And some, not all, but many of those immigrant communities from a country are somewhat spatially concentrated within Los Angeles, which creates opportunities to celebrate that country and culture in those areas. The city of Los Angeles has made some efforts to create cultural zones as neighborhoods with designations — Koreatown, Thai Town, Historic Filipinotown — that associate a place with the culture. But sometimes, because of the nature of Los Angeles, there's been gentrification, and people from that culture no longer live there. There's not always the equivalent of a zocalo or a gathering place for that community, which I think is really important during gentrification waves. Because too often gentrification means rising rents, and ethnic businesses are the center or the anchor of a culture in a community, rather than a public space.

This is exactly what we’re seeing in so many communities right now, especially with restaurants closing.

Rising rents means that those businesses go, and then there's really not the amenities that people from a country or culture were used to. And so then they disperse as well. Sometimes they all go to the same area. I'm most familiar with the Thai community in Los Angeles — my wife is Thai and her family was part of a group that migrated from East Hollywood to North Hollywood. But that was based on housing opportunities that were available 20, 30, 40 years ago in Los Angeles. People now migrate further and further away from these historic cultural centers.

In Los Angeles, we have the opportunity to activate spaces that already exist with programming and bringing in a combination of local businesses and artists and musicians to really make it a place that people want to be. And the creation of new spaces can be the acquisition of parklets and vacant lots and underused road space, maybe areas of a business district where people are primarily using the road to access parking that can be accessed from other streets. You could create a plaza out of that space and create those same opportunities for people to connect and celebrate a culture. We'll be showcasing Aaron Paley, who has these ideas of activating these spaces with arts and cultural programming. Aaron was a co-founder of CicLAvia and Community Arts Resources, who was involved in the LA '84 games, and really sees this opportunity to leave an arts and cultural legacy for people that's associated with places, and having that be truly multicultural in a way that I think LA will be much more comfortable with now than in 1984.

The Paralympics are underway in Paris and there’s one very important aspect of LA’s games that I've been trying to focus on, which I'm so glad to see on your agenda. Let’s talk about creating access for a city which continues to see lawsuit after lawsuit telling us that we have not built our city to be accessible.

In having conversations about the games with people involved in the planning preparations, I always ask them, what is not getting the attention that you think it deserves? And it's the same answer with many people: universal access for people with disabilities. That doesn't just mean putting in a ramp that meets some sort of slope requirements and width requirements, and saying, we've done it, yay! That means taking a more comprehensive approach, and often a more user-experience type of approach, where you consider the city or the sports venue or the building holistically — not just getting up some stairs, but from the perspective of somebody with limited mobility, or somebody in a wheelchair, or even somebody with some sort of cognitive limitations, because a lot of times, I've noticed that government makes things more complex in order to try to achieve some sort of equity outcome. Thinking about those things through the opportunities primarily of the Paralympic games, which are the last in the series of up to seven megaevents, you might know better than me —

I think you’re right — we’re doing seven megaevents.

— you can’t just say we have three weeks to make the city accessible, right? We needed to be doing it, starting in the ‘70s with the Americans with Disabilities Act. And it's a very slow process, particularly in the city of Los Angeles, because everything that involves money and capital planning and permitting coordination and council districts is a very slow process in the city of Los Angeles. That’s why we don't have ADA-compliant sidewalks in much of the city of Los Angeles. We're bringing in a speaker who's comprehensively studied ADA compliance in cities and wrote an article for the Journal of the American Planning Association about the pitfalls, limitations, and best practices for accelerating accessible design and accessible access for people. That’s Molly Wagner, who's at the Center for Neighborhood Technology.

And we also need a capital plan.

The one connection I wanted to make here is the importance of a capital plan. So this idea that multiple agencies of the Los Angeles city government would come together and prioritize infrastructure project requests over a five-year period or longer. The city could plan which of those it was going to fund, and they'd be coordinated between departments, rather than having them done haphazardly, and there would be substantial cost savings associated with the planning component of that. That idea is one that we're going to explore at the symposium, because one council district, CD 8, and Destination Crenshaw, have tried this approach of, hey, maybe with some planning, we can get more done with the same amount of money. Or, maybe, with a little bit more money, because you attract more money when you’re smart about how you spend it. That is probably the biggest limitation to so many of these legacy projects in LA that involve public money in the public realm.

It seems pretty simple. We just need to make it easy for people to get places, both from an accessibility standpoint, and also as part of an extremely basic tourist experience. And then we also need to make sure these are places that Angelenos can keep enjoying every day after August 27, 2028.

One thing to think about is if we do well at this, and all of these megaevents leave the city better, and people have that impression, there will be more megaevents. This will just be part of our identity. 🔥