The transit-first (no, really) games

In the end, LA28 put the events where the public transportation will already be

A report from last month's UCLA Lake Arrowhead Symposium, intended to both illuminate existing challenges and light a path forward for progress, reveals deep frustrations and grave concerns about LA's megaevent planning

"Let's create light," urged Juan Matute, deputy director of UCLA’s Institute of Transportation Studies, at the convocation of last month's UCLA Lake Arrowhead Symposium, entitled Mega Events: Major Opportunities. He was standing before the event's graphic — a hand holding a torch as Angelenos frolic across a map of the region — but in reality, the 2028 Summer Olympic and Paralympic Games are only one of many major opportunities confronting Los Angeles. The next four years will bring an astonishing total of seven megaevents to Southern California, with more being scheduled all the time. And up here, with 5,100 feet of perspective, Matute intended to shine a beacon onto the increasingly urgent conversations questioning LA's lack of vision, the vacuum of leadership, and why the public-facing planning for our impending megaevent era feels scattered, opaque, and, at times, counterintuitive to our goals as a region.

"In 60-plus conversations with folks as I was preparing for the symposium, I saw there was a discussion happening behind closed doors and it would be better for Los Angeles if it happened in a more open forum. Now it’s more out in the open," says Matute, who I first spoke with in September about the goals of the event. And a just-published report on the symposium, intended to both illuminate existing challenges and light a path forward for progress, reveals deep frustrations and grave concerns about LA's megaevent planning.

The symposium drew 170 attendees, including people from public agencies, private firms, academia, nonprofits and advocacy groups, and representatives of what I'll call the "big three" megaevent producers: LA28, Metro, and the office of LA Mayor Karen Bass. Several LA elected officials were invited but none of them attended, although some sent staff members. And just a note here about how I reported this story: to adhere to the symposium's rules, which are detailed in the report, I have not attributed what was said at the event, instead, I reached out to attendees after the event to get these quotes on the record.

Simply organizing an event about megaevents provided its own lessons, says Matute. "Despite our preparations to ensure the facilities complied with the Americans with Disabilities Act, we realized that this was insufficient to accommodate some of our most valued speakers who would offer perspectives on the need to include people with disabilities in planning processes." Additionally, as noted in the report, the event's graphic did not expressly depict disabled people. "We will learn from these oversights and work to have more inclusive events and graphic design in the future," Matute told me. "We urge others responsible for gatherings, including megaevents, to be more proactive in accommodating and including people with disabilities."

These systemic failures — and the class-action lawsuits that follow them — are similarly pervasive across LA's public infrastructure, recreational spaces, and transportation systems; essentially, everything that's required to host a megaevent. These lessons set the tone for the symposium early on, so much so that a topline recommendation in the report urges megaevent organizers to "comprehensively consider the accessibility needs of individuals with disabilities, based on their direct inclusion in the planning process." This can only be achieved, as was also noted frequently during the event, by placing disabled people into key leadership roles. As Candace Cable, a Paralympian and member of LA's Commission on Disability, framed the challenge: "If you are going to bring people who have been ignored into the fold, then significant change is required — are you committed to disrupting the status quo?”

The status quo — and the cascading crises of overworked staff and budget shortfalls facing local governments — seems primed for disrupting. Unfortunately, LA, as a region, currently lacks the planning coordination to leverage megaevents into long-range future benefits, says Anastasia Loukaitou-Sideris, urban planning professor and interim dean at UCLA's Luskin School of Public Affairs. "In a region where decision-making and planning are often fragmented and siloed, I expressed my concern that we have not heard, thus far, about a strategic planning effort that would bring different parties together to articulate the vision of what should be achieved in that regard, and the means and strategies to do so."

Loukaitou-Sideris's concerns were echoed by her fellow panelist, Genevieve Giuliano, public policy professor and interim dean at USC's Sol Price School of Public Policy. "My bottom line has been about leadership," says Giuliano. "LA28 says this is what we’re doing, Karen Bass says this is what we're doing, Metro says this is what we’re doing — that reflects to me the lack of coordination and the lack of an entity or a group that’s pulling them together. There has to be coordination and cooperation among all of the lead players, public and private."

For those keeping track, that's two deans of two public policy schools at two major LA universities sounding the alarm about the region's lack of leadership.

One example of what Loukaitou-Sideris and Giuliano describe is the growing rift between the people who are describing the 2028 Olympics and Paralympics as the "car-free" games versus the "transit-first" games, a phenomenon I noticed back in July. These are two very different goals with two very different outcomes and it does matter what we call them. (Although one Metro representative did say "car-free, transit-first" games, which I'll accept!) Giuliano is actually the expert on this; she's the author of the now-famous report on the 1984 games which outlined in detail how organizers radically reshaped the region's transportation systems for a few weeks — and how basically none of those changes, recommended by a SCAG-convened group named the Olympic Legacy Task Force, actually stuck. In an attempt to ensure this legacy doesn't slip through LA's fingers, a dedicated portion of the symposium focused exclusively on how to get more lanes — bus lanes, but also lots of talk about freeway lanes and bike lanes — so the infrastructure to move millions more people for a few weeks doesn't vanish in 2029. This time, can we keep them?

But although many transportation elements of LA's megaevent legacy will stick around — thanks in large part to Metro, which has taken its planning role extremely seriously — symposium attendees were reminded that new housing and public spaces were also once part of the plan for hosting the Olympics and Paralympics. The original bid document assures Angelenos that the organizing committee will create "new community green spaces" and "after the games, these spaces will contribute to the expression of our diverse communities, and provide access for Angelenos to be active and healthy through additional sports and cultural programming." In 2015, the organizing committee even touted the building of a brand-new Olympic Village as a "significant legacy opportunity for our city after the games" with "17,000 beds for the athletes, coaches and staff, which would then be converted into 5,000 units of both affordable and market-rate housing." Clearly there are no new parks being planned for 2028. (At least, not yet.) And the promise of affordable housing vanished when the organizing committee made the decision to house athletes and media in existing dorms at UCLA and USC instead. In fact, any guarantees of an affordable housing legacy were upended when the IOC signed an international partnership with Airbnb, which is actively recruiting 100,000 more LA-area hosts in advance of 2028, and where the city of LA currently lacks a short-term rental enforcement mechanism.

These were pledges made to the people of LA as a condition of hosting these megaevents — and they need to be honored, says Kurt Petersen, co-president of Unite Here Local 11, which recently sent letters to the leaders of LA28, the Los Angeles World Cup Host Committee, the IOC, and FIFA urging them to endorse a $30/hour minimum wage for tourism workers known as the Olympic wage. "We are calling for a New Deal for the Olympics," says Petersen. "First, it must be democratic and transparent. No more backroom deals with billionaires. Second, we must harness the immense opportunity presented by the billions of dollars in economic activity generated by these events to create livable jobs, affordable housing, and equal justice."

To do so would require genuine community engagement from the megaevent organizers, which Angelenos have yet to see, says Katherine Perez, who recently co-founded the new nonprofit Los Angeles Tomorrow, in part, to work with neighborhoods that won't see games-related activity. "There is no vision," Perez says, "because there has been no engagement about our hopes and aspirations for the Olympic and Paralympic Games." But that could be easily remedied, says Karen Mack, CEO of LA Commons, the South LA-based arts and cultural nonprofit. "It seems like everyone's on the same page in focusing on neighborhoods and focusing on culture," she says. "What's amazing about culture is it's a vehicle for engagement and that's really what our work is about: using that opportunity to uplift people's stories as way to bring them into the civic process."

Just in the last few weeks there have been a series of positive civic process announcements. Bass signed Executive Directive 9, which will enable the city to finally do long-term capital planning for public infrastructure, with a pointed focus on accessibility. And at October's Metro ad hoc Olympics and Paralympics committee meeting, board members passed motions paving the way for unprecedented regional coordination including a new megaevent transportation summit, potentially signing a separate games agreement with LA28 to clarify expectations, and another pointed focus on accessibility. Clearly, the single greatest outcome of our megaevent era would be forging meaningful cooperation to produce not just a car-free games, but a universally accessible games, and at the same time positioning disabled leaders as the infrastructural decision-makers permanently. With accessibility championed as LA's legacy, nearly everything else would fall into place. But who would lead such work?

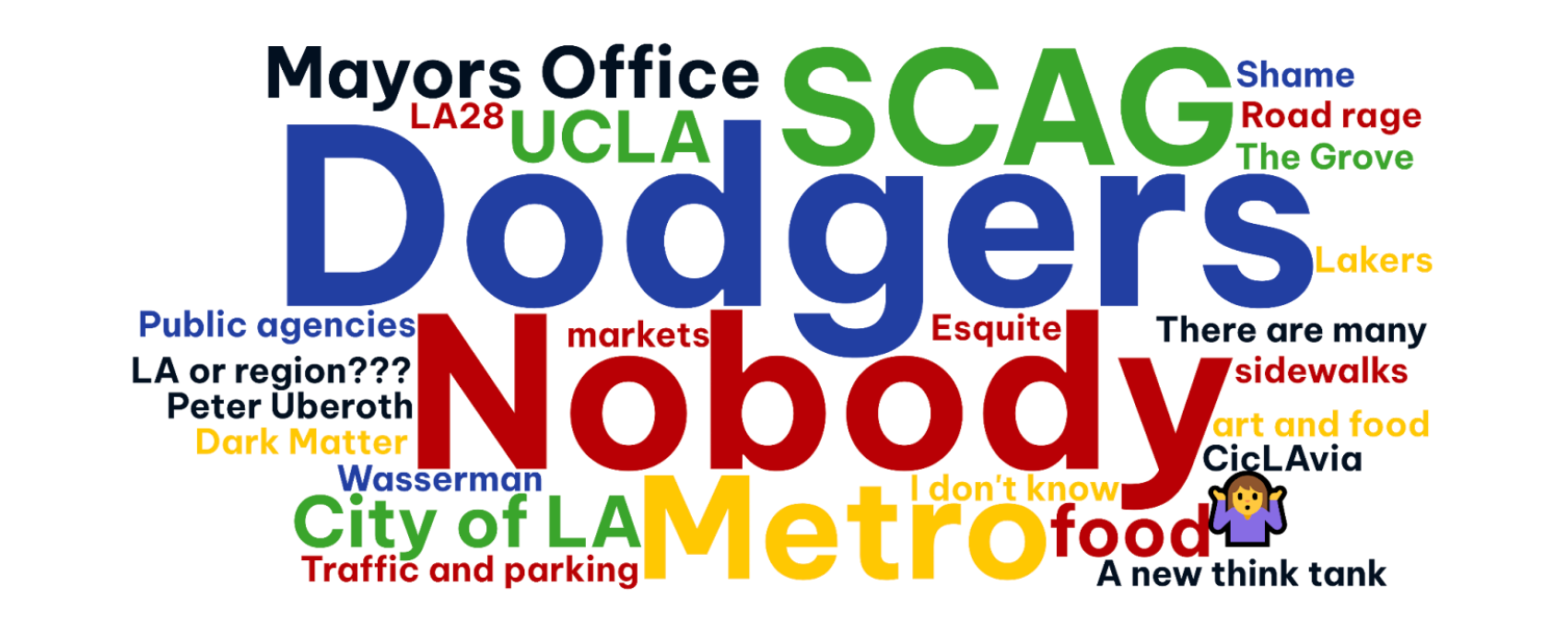

While attendees were at the symposium, the Dodgers were finishing off the Mets in the National League finals. The playoffs aired on a big screen during happy hours; baseball was on the brain. It's important context to have as I show you the answers to one of the symposium's final crowdsourced questions: What entity brings everyone together in LA?

Since the Arrowhead report has been drafted, the Dodgers have won the World Series and planned a championship parade and sold-out rally at the Dodger Stadium, both of which are happening today. World Series parades have historically been among the largest gatherings in U.S. history, and pending attendance estimates, this celebration potentially adds an eighth megaevent to LA's lineup — one conceived, coordinated, and executed within a matter of days. Unlike last Friday's "traffic nightmare" overhyped by local media who have no idea how transit works, today's events may be the first true test of the region's megaevent capacity.

But, as the report asks, what can bring LA together, aside from the Dodgers? What's perhaps more striking to me when I look at the answers is not necessarily that the Dodgers are #1. It's the other top answer: nobody. 🔥