Traci Park's Olympic parking lot

A notoriously anti-bike lane councilmember is using the "car-free" games to stop a fully approved 100 percent affordable housing development

Before everyone spins Kathy Hochul's cowardice into a death knell for LA's congestion pricing dreams, it's important to know that there are lots of different ways to do road pricing

One of the things I was most looking forward to writing about in this newsletter was the runaway success of New York City's congestion pricing program. By charging drivers to enter Manhattan below 60th Street, the small number of people who use cars to reach New York's central business district get a faster trip into the city, and everyone gets cleaner air, safer streets, and $1 billion annually for much-needed MTA improvements. It was all set to start June 30, until yesterday, when it wasn't, because New York Governor Kathy Hochul called for an "indefinite" pause of the program in a surprising — but not altogether out of character — last-minute policy reversal. While this is certainly bad news for New York, the repercussions here are nationwide. Hochul's shameful decision to blow up the most powerful piece of climate policy in New York City's history leaves cities like LA wondering if our own congestion pricing plans will ever see the light of day.

Congestion pricing has been exceedingly effective wherever it's introduced — London, Singapore, and Stockholm have all famously not imploded — but it's never easy to implement, even in cities like New York where a majority of people ride transit. Interestingly enough, in LA, the concept has been most seriously broached within the context of Olympic planning. "We think that with congestion pricing done right, we can be the only city in the world to offer free transit service in time for the 2028 Olympics," former Metro CEO Phil Washington said at a 2018 Metro board meeting. Charging drivers to pay bus fares is kind of a lovely thought, although it's not really necessary here; fares only make up 4.8 percent of Metro's operating budget, so the agency could make transit free, fiscally speaking, at any time. Tying it to something like the Olympics is pretty smart, too. Having a system in place to charge drivers to access popular areas during a megaevent could collect major revenue, reduce traffic around venues, and persuade attendees to take the free transit instead of driving. This particular concept for 2028 never went anywhere — but it certainly wasn't the worst idea.

Metro continues to study congestion pricing but getting political consensus remains difficult because LA's population remains extremely car-dependent without the necessary investments being made in alternatives to driving. But my way of thinking shifted on this in 2021 when I talked to Michael Manville, associate professor of urban planning at the UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs, for a story unfortunately entitled "What It Will Take for Kathy Hochul to Get Congestion Pricing Right." (I mean, a backbone, amirite?) He said something that has always stuck with me: congestion pricing is actually really great for drivers. "In a way, it's one of the most pro-driving policies," he told me. "If you choose to be in your car, you are paying with your money or your time. Here, you will pay something, but you will actually get good service in return." This is why congestion pricing, once implemented, is very popular, as any person who thinks about transportation for a living will tell you. But, as we know, officials who make decisions about transportation prefer to get their information from unspeakably irresponsible reporting by local media.

But before everyone spins Hochul's cowardice into a death knell for LA's congestion pricing dreams, it's important to know that there are lots of different ways to do road pricing. New York City's plan — which will get done someday — is called "cordon pricing," meaning it's a circle drawn around a zone, and you're charged when you cross the boundary. Other versions of road pricing can mean you're charged to use freeways or even for the number of miles you drive. And it might surprise you to know that LA already has one of the U.S.'s most successful road-pricing programs. Metro’s ExpressLanes system charges drivers a variable rate to use dedicated lanes on the 10 and 110 freeways. This money — $100 million raised in the first decade — gets invested back into transit along the same corridor, which is used by the bus rapid transit Silver (J) line and the FlyAway to LAX. Road pricing makes buses go faster.

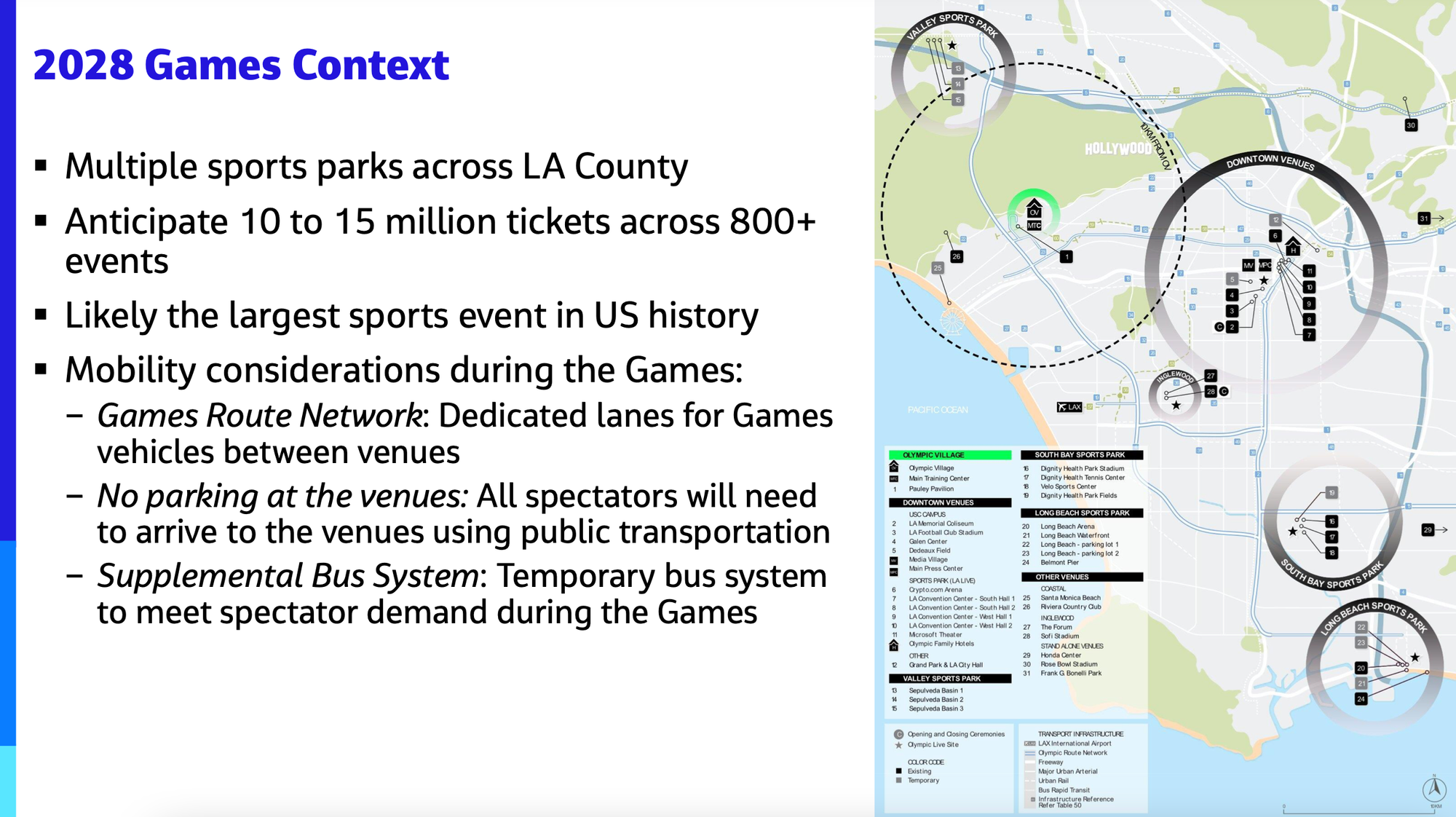

What Metro's now planning for 2028 borrows from the ExpressLanes concept. The proposed Games Route Network is a series of dedicated lanes connecting venues all over the city where vehicles carrying Olympic-related passengers can easily zip around LA. The lanes are necessary to make sure the Olympics actually happen — "if athletes can't get to the event, there are no games," one Metro presentation warns — and can also help keep our temporarily beefed-up bus fleet out of traffic. Particularly on freeways, where 80 percent of the network is located, these temporary lanes will function as something LA could really use on a typical Friday afternoon: a countywide dedicated lane network. On the freeways, these lanes could be hypothetically converted into everyday ExpressLanes by September 1, 2028.

The window is closing for legacy projects, but Olympic lanes are an ideal one: low cost, in place the day the games end, many Angelenos already have the transponder in their car! And once we have a network of lanes, Metro can unlock bigger regional goals. London's congestion plan is constantly evolving: it started in 2003 to curb traffic in the city center and has since morphed into an Ultra Low Emission Zone that encompasses the entire city, significantly reducing air pollution. That sounds like a pretty great legacy for Angelenos who breathe the worst air in the nation — and the officials who claim they want to do something to help them. The 1984 games, after all, were structured around a different congestion-reduction strategy, which temporarily eliminated traffic. But after the Olympics, LA's leaders let it all evaporate. Maybe this time, they won't. 🔥