The transit-first (no, really) games

In the end, LA28 put the events where the public transportation will already be

There are hundreds more public spaces just like MacArthur Park all over the city that won't ever get this level of attention because they're not catty-corner to a famous business

On Saturday, Norm Langer told Los Angeles Times columnist Steve Lopez that he was considering closing his 77-year-old deli across the street from MacArthur Park. The situation had become untenable, Langer said, citing excessive trash, homelessness, public drug use, and extortion from local gangs, although he clarified he didn't think his staff or customers were ever in danger. On Monday — Langer's, as anyone who has woken up craving pastrami and eggs knows, is closed on Sunday — Langer upped the stakes, saying he would shut down within a week if the city didn't take action. By the next day, LA Mayor Karen Bass was seated across from Langer at a wood veneer booth, an agreement being brokered over a bowl of dill pickles. Langer later said he will stay open, but if he doesn't see changes within the next week, "I will lock the door."

At one point in Lopez's story, Langer walks Lopez across 7th Street to the Westlake/MacArthur Park B line (formerly Red line) station. Here, Langer is immortalized in the public artwork Urban Oasis, 13 mosaic panels which Sonia Romero created in 2010 to "celebrate the 120-year-old history of MacArthur Park and the people who make use of it." Just one year ago, Langer said that in 1993, during another difficult time in the city's history, the opening of this very subway station saved his business. Not the Jonathan Gold review in 1991, although that helped; what brought Langer's back from the brink was a billion-dollar investment in the public realm.

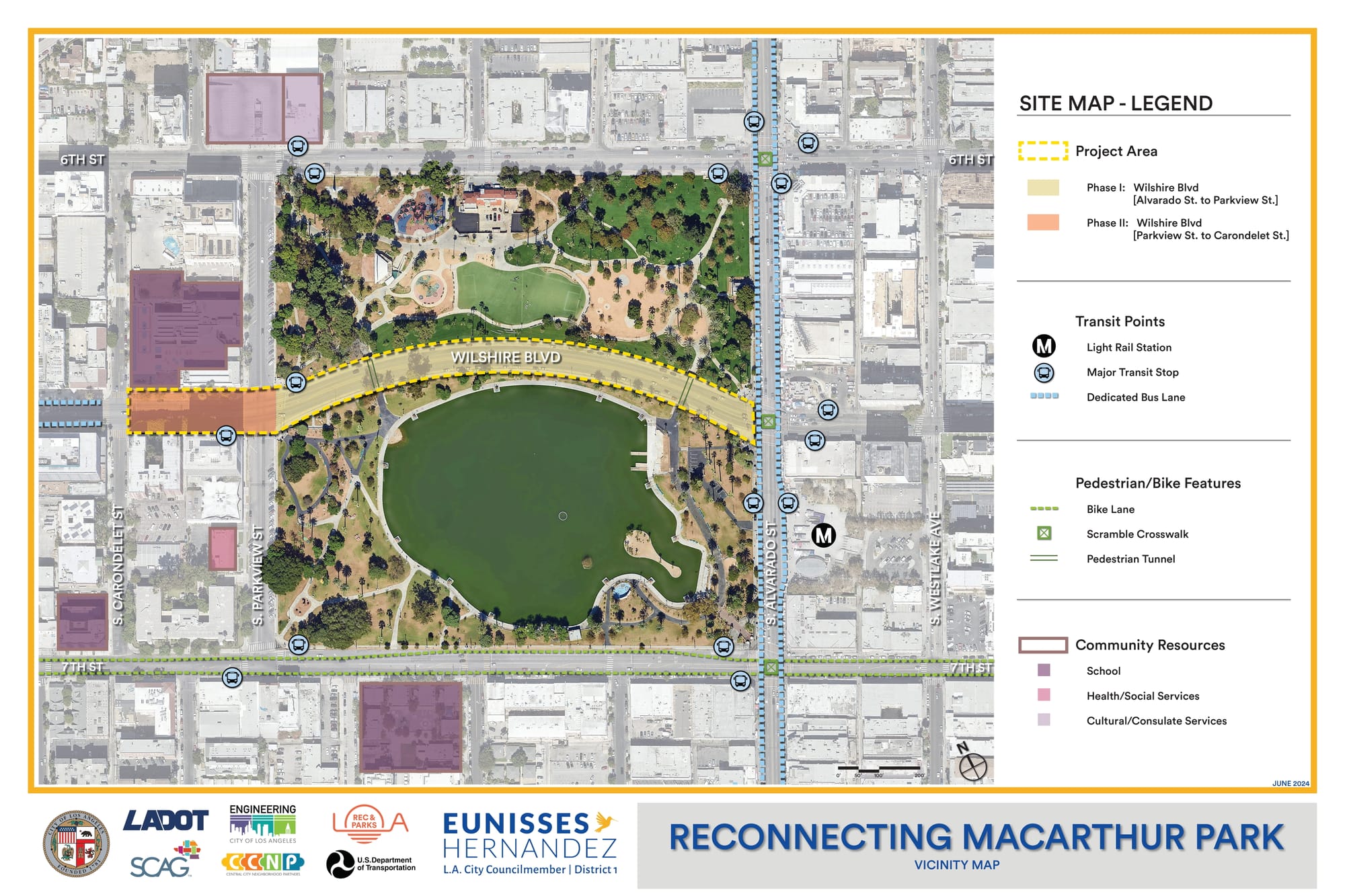

Despite this week's headlines, as you cross Alvarado — on one of three scramble crosswalks installed here by the city due to the large numbers of pedestrians — it isn't that difficult to find the park vignettes depicted in Romero's panels. It feels like there's always a soccer game happening on a nice pitch in the northern side of the park, where the rocks are painted yellow like egg yolks. Kids screech down a two-story slide on a huge new playground. A saxophonist jams on a bright blue bench. There are ice cream vendors. Fishermen. Canadian geese. Lots of people undoubtably escaping their un-air-conditioned apartments on a very sticky August day, and some who may not have an apartment to return to at all. Parents picked up their students from one of two LAUSD elementary schools adjacent to the park. Along 7th Street, a group of teens on ladders painted a mural. Just a few weeks before, Stevie Wonder appeared onstage here during a tribute to his music at Levitt Pavilion, which hosts concerts in a mini-Hollywood Bowl bandshell every summer Saturday night. Tomorrow's the last show of the season, you should go!

The challenges Langer described are happening in MacArthur Park, too, and they're certainly not new. But these are challenges citywide; I live 1.5 miles away and the same things are happening in public spaces by me. One thing I strongly agree with Langer about is how much LA's general cleanliness has deteriorated just in the last year: filthy gutters, grimy sidewalks, and tagged-up alleys awash in drifts of trash. Walking through many neighborhoods in this city has become an exercise in wading ankle-deep through garbage.

Langer says one reason things have gotten so bad is that there's fewer cops patrolling now — "What is the point of having a law if you’re not going to enforce it?" he asked — and he insinuates it's because of efforts to defund the police. (Which, to be clear, did not happen.) This is a wild thing to say because if I wanted to find a cop in MacArthur Park I would know exactly where to go: Langer's. When I'm there for lunch — #19, a cup of matzo ball soup if it's cold out, fries, pickles, coke — I see them in uniform, along with at least one or two city employees, the odd city commissioner, and sometimes even an elected official. Nothing in that story about the state of 7th and Alvarado will surprise anyone with the power to address the issues, because I've seen them gingerly stepping around the issues on their way back to their car.

The claim that the cops aren't around also surprised me because the police presence is now pretty much constant at what's probably the most closely monitored Metro station on the entire system. The Westlake/MacArthur Park station became internationally famous last year when Metro deployed Guantanamo-style torture tactics by blasting classical music on the platform to prevent people from loitering. But aside from the free underground concert, the station experience has significantly improved; as I've written about recently, the subway is cleaner than it's ever been. The plaza now has bathrooms, on-site resources, and helpful unarmed ambassadors milling about. Why? In part because powerful people — who weren't necessarily passengers — complained. But also because Metro has money. Measure M was approved by taxpayers in 2016, bringing in nearly $900 million annually to ensure that public transit remains reliable, accessible, and, most importantly, usable.

And that's the part that we really need to talk about here if we want anything to change. Because for all the reporting heaped upon this issue over the past few days, the coverage has neglected to mention one thing: MacArthur Park is a 35-acre, city-owned public space. And while LA's police department hasn't been defunded, the parks department has.

As I mentioned in a story earlier this month about how the city is being sued for accessibility violations in its parks — for those keeping track at home, that's people with mobility disabilities suing LA over both parks and sidewalks — Proposition K, the city's park bond, is expiring in 2026, and there's no plan to replace it. A very overdue needs assessment has yet to be conducted. Many park positions were eliminated. And it’s not just parks, the maintenance of our sidewalks and streetlights and urban canopy is careening off a fiscal cliff, because the city has effectively abdicated its role in managing public space.

There is a plan for MacArthur Park, and part of that plan includes potentially kicking cars off Wilshire Boulevard to expand the park's footprint in a neighborhood that only has .5 acres of open space per 1,000 residents. (The city average, which is admittedly not great, is 8.9 acres per 1,000 residents.) Whether or not this is the right solution — and some local residents do not like the idea — this is $2.5 million in federal funds (not city funds) to study what public space improvements the neighborhood needs, including safety elements like new lighting. And it's only one part of what's being done. The new playground on the southwest corner was installed — in lightning-fast time, I should note — in part because families didn’t feel safe walking to the playground on the north side of the park. Another new playground is being installed two blocks south of the park for the parents who don't feel safe going to MacArthur Park at all.

But we can't just landscape our way out of chronic disinvestment. Langer mentioned a $1.5-million revitalization project during the pandemic where the improvements "went down the drain." To be clear, this was not a revitalization project, this was a time when local councilmembers went on a fencing-off frenzy to keep anyone from using parks at all. The reason it didn't "work" was because the park reopened with fresh sod but no additional amenities to offer the people who had nowhere else to go. Under Councilmember Eunisses Hernandez, who was elected in 2022, the park now has $3 million in opioid settlement funds and a USC street medicine team — something I know about because I reported on it, but you can go to the park and see the team out there helping people (which I can't always say is true for the cops). The need is so great that fixing LA's parks will require both infrastructure and investments in services, and, most importantly, Measure M-level money.

I'm sure there will be tidy follow-ups on how the city acted quickly to highlight solutions addressing Langer's issues with the neighborhood. (And hopefully without criminalizing the vendors who rely on the park's foot traffic for their livelihood.) But there are hundreds more public spaces just like MacArthur Park all over the city that won't ever get this level of attention because they're not catty-corner to a famous business. At this point, everyone is well-versed in the mayor's clearly articulated vision to confront the crisis that's forced people to turn LA's public spaces into their homes. But once the city gets people inside and safe — and, critically, into their own permanent homes — what we're missing is the mayor's vision for how to turn those public spaces back into places that actually serve the public.

And the public needs them. There's been a lot of talk among LA officials about making our global sporting megaevents more accessible to Angelenos by hosting viewing parties and fan festivals in centralized gathering places. MacArthur Park is the absolute best candidate for this kind of permanent intervention, not just in time for the Olympics in 2028, but also, perhaps even more critically, for the World Cup in 2026. This is the urban oasis the most densely populated neighborhoods in the city deserve. But it won't happen until the leadership of this city decides that both our small businesses and our public spaces are actually worth saving. 🔥