Winning streak

It's past time to expand LA's celebratory capacity to match the records of our world-champion teams

When the news renders you speechless, you can always find a response that Corita already ripped from the headlines

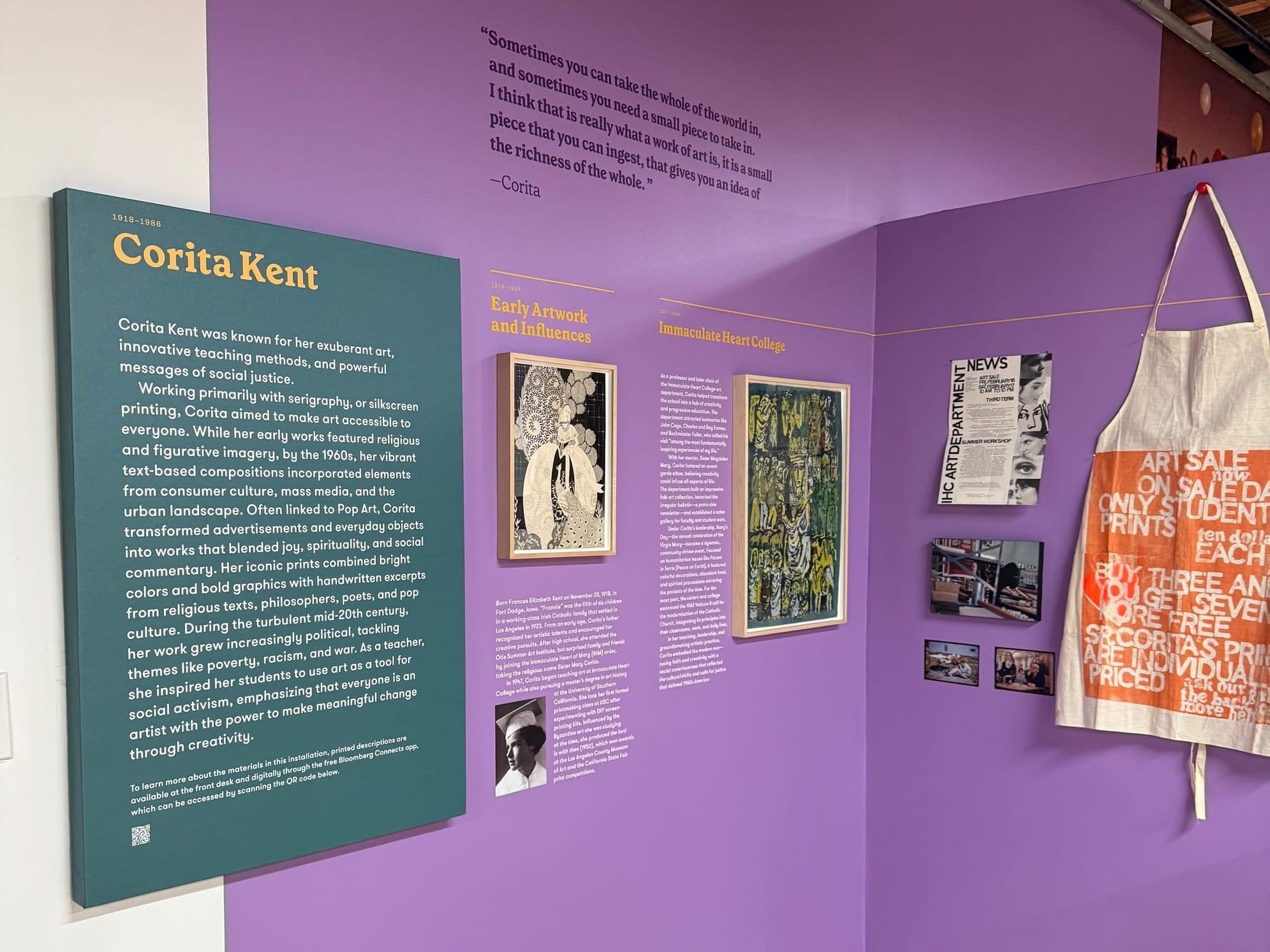

On a drizzly day two months after the worst disaster in Los Angeles history, I stood in the Arts District reacquainting myself with the work of Corita Kent. I'd consider myself a superfan of Corita, as she was known, the "pop-art nun" who operated an internationally acclaimed art school at the southern edge of Griffith Park in the '50s and '60s. But during these fraught times — are there any not-fraught times anymore? — Corita had once again surged into my consciousness with fresh urgency.

As I flicked unsettling news alerts off my phone, I took in the technicolor serigraphs with narration from Corita Art Center executive director Nellie Scott. "When she uses that smaller script," Scott noted, "it's because she wants you to come in closer." I nudged toward a passion for the possible, its black-on-gold silhouetted hands flashing peace signs at a rally. Rendered in Corita's distinctive script was an interview with Presbyterian minister and anti-war activist William Sloane Coffin: "Realism demands pessimism but hope demands that we take a dim view of the present because we hold a bright view of the future."

Then, in chunky all-caps serif: "HOPE AROUSES AS NOTHING ELSE CAN AROUSE A PASSION FOR THE POSSIBLE."

"heroes and sheroes" features 29 prints made by Corita using covers of magazines like Life and Newsweek

Hope is the thread that binds Corita's body of work. In fact, it was her piece entitled hope that was selected for the billboard announcing that this spring, after many years of uncertainty, the Corita Art Center would reopen at a permanent address on Traction. This milestone is made even more poignant at a time when many artists in the center's orbit have lost their own studios, schools, and homes. During the fires, as the center distributed art kits to children who had been displaced, Scott was overwhelmed with messages from people all over LA who said when they evacuated, they packed up their Corita prints along with their go bags.

Corita is known for her bold, fluorescent graphics, but, at its heart, this is word play. To create these lyrical connections, she snatched snippets from everywhere: clipping type from freeway signage and slicing up supermarket ads. Her ability to juxtapose the monumental and the mundane often resulted in pointed social commentary. For my people, made during 1965 Watts Rebellion, Corita flipped the overtly racist front page of the Los Angeles Times on its side and flooded the page with red, using her small script for a call-to-action from Maurice Ouellet, a Catholic priest and civil-rights activist in Selma. It remains an hauntingly appropriate message for an LA struggling to recover from catastrophe. Eight weeks after the city was showered in the singed fragments of books and magazines, Corita's work challenging us to make meaning from jagged-edged, out-of-context text delivers even more of a gut-punch.

And that's really the thing about Corita. When the news renders you speechless — as I think we are experiencing all too often over the last two months — you can always find a response that Corita already ripped from the headlines. As Scott, a tenacious protector of Corita's legacy who is acutely aware of how the work meets the moment, said to me, years before our current crises: "I watch the news every morning, then go to work, and whatever quote I need is there."

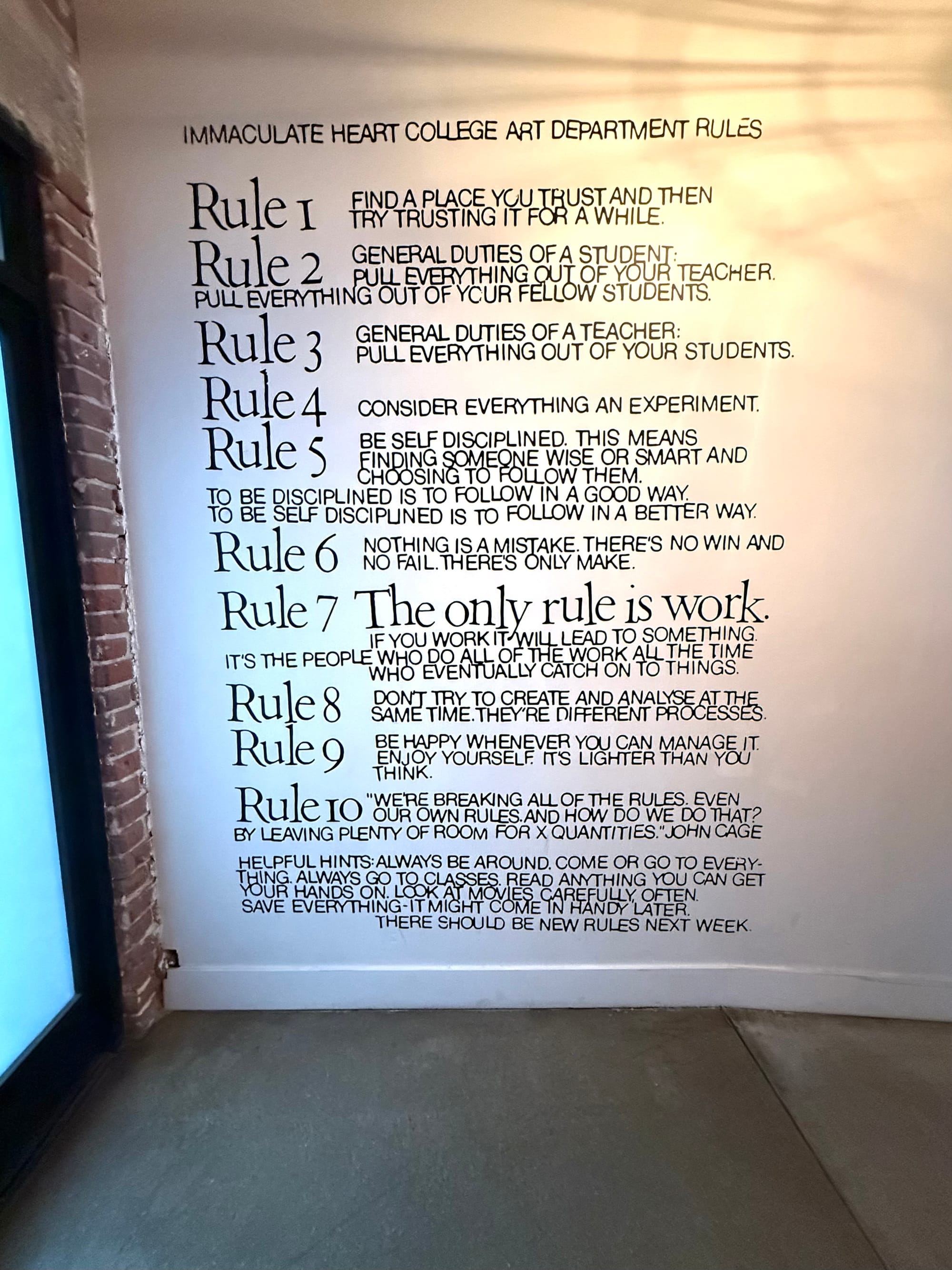

For many years, Corita ran the Immaculate Heart College art school at Franklin and Western in Hollywood. Under Corita's leadership, the high-visibility corner transformed into a community center that held art sales and staged joyously exuberant celebrations on the lawn. Torched readers will find this visual language quite familiar; a very short line can be drawn from the brightly painted towers of cardboard boxes to the low-cost, high-impact design of the 1984 Summer Olympics. Before the games, graphic designer Deborah Sussman worked in the office of Corita's longtime collaborators Charles and Ray Eames, who were frequent guests at the school and hosted studio visits for students. In the 1985 issue of Design Quarterly, architecture critic Joseph Giovannini writes that Sussman's Olympics designs were "taking inspiration from such disparate sources as Sister Mary Corita's religious processions at Immaculate Heart College in Los Angeles in the 1950s, used car lots, and even everyday signage."

When Corita died in 1986, she left her body of work to what would become the Corita Art Center. The archive was housed in a cramped hallway on the Immaculate Heart campus, now a high school, where, for many years, you could walk in and purchase an original serigraph selected from a flat file. In 2021, Corita's studio, a small white box across Franklin, was declared a historic cultural monument, protecting it from imminent demolition. (And ever-so-slightly boosting LA's appalling women's heritage record; only 3 percent of the city's monuments honor women.) That preservation battle accelerated the search for a more publicly accessible home for the center, with proper storage and room to host programs and exhibitions. With Corita's work so often exhibited in bustling museums, this intimate space, staffed with experts on her life, is the ideal setting to really zoom in.

Corita's oft-cited rules are found near the entrance; perhaps her most famous work, yes #3; in the hallways where some of Corita's works have been recreated as supergraphics in collaboration with the legendary sign-painting department at LA Trade Tech; "circus alphabet" installed in the conference room

The center's first exhibition is "heroes and sheroes," 29 prints that Corita made in 1968 and 1969, during a time of personal and political upheaval. Starting in 1965, the Vatican had ordered modernizations to clothing, language, and mission that Immaculate Heart embraced as part of a social justice agenda. Corita, appearing on the cover of Newsweek with the headline "The Nun: Going Modern," became the face of the reform movement. But LA's hyper-conservative archdiocese retaliated against the "unruly flock" on Franklin, a story captivatingly told in the 2021 documentary Rebel Hearts. Eventually, a group of Corita's sisters renounced their vows, creating the inclusive, ecumenical Immaculate Heart Community. Amidst the turmoil, Corita took a sabbatical on the East Coast in 1968, then, in 1969, left the order as well. Her work, already topical, became visceral as she chronicled one of the most tumultuous eras in U.S. history alongside the revolution brewing within her own faith. phil and dan shows two of the Catonsville Nine, a group of Catholic activists in Maryland who burned Vietnam War draft cards, a significant act of protest. This series was Corita's resistance; a registering of the growing sense of fury from those who felt betrayed by, as the wall text notes, "a nation that has lost its way."

In her art classes, Corita urged her students to use a "finder" to crop a panoramic view into a tiny frame. A finder could be an empty 35mm slide — Corita's remarkable photography is collected the book Ordinary Things Will Be Signs for Us — but any piece of card stock with a cut-out will do. A set of custom-made finder postcards are helpfully stacked at the center's front desk, stamped with a Corita quote which, once again, urges visitors to take a closer look.

A finder, available at the center's front desk; biographical information and artifacts from Corita's life on permanent display

But upon this visit to Corita's forever home, I saw something new. Just in the short time I stood within the center's colorful walls, the screen in my pocket became stacked with mounting emergencies. In our current situation, the big picture dominates our attention — collapsing homes, collapsing communities, and, increasingly, a collapsing democracy — overwhelming us to the point of inaction. Picking up a postcard from the desk, my finder landed on a Corita quote across the room: "Sometimes you can take the whole world in, and sometimes you need a small piece to take in."

My field of vision was currently filled with screenprinted hearts; I didn't want to return to the reality outside. But now I had a tool. When faced with the incomprehensible scenes before us, Corita's work urges us to focus on the one small piece of the world that feels solvable. Or perhaps, simply, possible. 🔥