The Grand scheme

This is the downtown that Frank Gehry wanted. When will LA's leaders give it to us?

It's impossible to prepare yourself for the onslaught of data about the firestorm that has engulfed LA County: acres burned, households evacuated, structures destroyed, and tragically, lives lost. But all you really need to know is that what has unfolded over the last two days is the absolute worst-case scenario. The other big one. Unfathomable, unreasonable, unstoppable, and, yet, inevitable — walls of flames bellowing into the city, feeding off our catastrophically desiccated landscape, lobbing embers deep into neighborhoods that flit from house to house to house, leaving nothing but ashes behind.

This is the story I never wanted to write. Reporting from a city, torched.

I began Wednesday morning by picking my kids back up from school, which was astonishingly not canceled, until it suddenly was, hours after we'd walked there under those all-too-familiar Tatooine skies. I felt good about sending them to class because their HVAC system — upgraded during the pandemic — offers better air purification than our drafty century-old Craftsman, which has been permeated by a scent unlike anything I've smelled in two decades of living in LA. The sun never rose, it simply appeared hours later, a glaring white spotlight cast through a narrow sliver of blue sky I could only see from my roof. The rest of the horizon was filled with two types of smoke: the cream-colored puffs of the Palisades Fire streaking to the southwest, the Eaton Fire a wall of swirling impenetrable gray to the northeast. Outside, a few miles from flames, it was dicey but not dangerous: we coughed behind our masks, nudged a downed western redbud limb off the sidewalk, and watched as sanitation trucks hoisted bin after bin filled with the serrated claws of fallen palm fronds. I told you palms were the worst.

As my readers know, what if the Olympics were happening right now? is a question I ask myself almost every day. On Tuesday, I planned to write a story about one of my favorite topics: how the perennial issue of evacuations and traffic management held lessons for our "car-free" games. I had great visuals, too. Steve Guttenberg warning his neighbors to leave their keys when fleeing their vehicles and bulldozers shoving abandoned Porsches to the curb so the firetrucks could access burning structures. But then the winds roared, the air quality plummeted, the ash began to fall. It quickly became very clear that two entire LA communities, Pacific Palisades and Altadena, were being swept off the map.

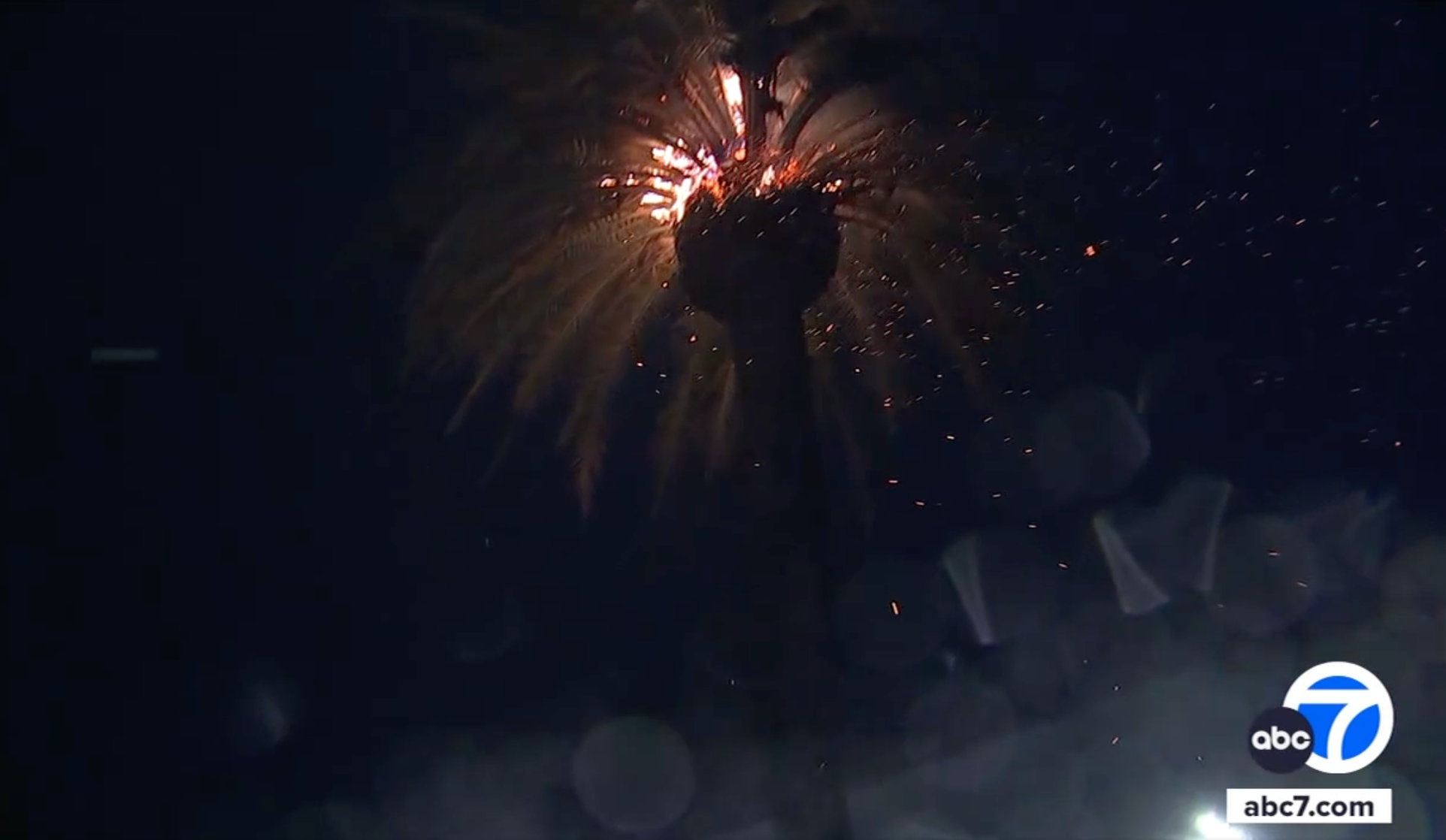

By nightfall Tuesday, watching local news feeds of eucalyptus trees immolating into showers of sparks as residents with belongings strapped onto bike frames raced past charred cars, the number of people I knew who were evacuating doubled, tripled, quadrupled. Then, a new tally began: the number of friends who have lost their homes.

Wildfires are regular occurrences in certain LA neighborhoods; just last month, in similarly high winds, the Franklin Fire charred the same swath of Malibu as the Woolsey Fire did six years ago. But these fires are descending like blowtorches from the foothills and into the strip malls. And when you've surrendered your society to fossil fuels, the scientific consensus is that there isn't much that anyone can do when faced with such extraordinary weather conditions. As UCLA climate scientist Daniel Swain, my go-to source on such topics, said during one of his extremely helpful livestreams: "When you have bone-dry, critically dry vegetation, 50 to 90 mile-an-hour winds, with highly flammable structures densely intermixed with the vegetation, there isn't a lot to stop the aggressive chemical reaction that is the combustion process of an intense wind-driven fire."

There was still plenty of finger-pointing. With Mayor Karen Bass on a presidential delegation to Ghana when the Palisades Fire began Tuesday morning, Rick Caruso — whose Pacific Palisades mall appears to have emerged unscathed, how? — unofficially kicked off his 2026 campaign for mayor by ringing up every local news show to make unfounded accusations about the city's response. Example: his claim that hydrants ran dry, even though LAFD chief Kristin Crowley — who famously saved an entire Malibu subdivision during the Woolsey Fire with her partner and some garden hoses — noted that wildfires notoriously wreak havoc with water pressure; pumping pools is much more reliable. One would think Caruso, a former Department of Water and Power commissioner, would know this.

But by then the chance for LA leaders to seize the narrative had vanished in a plume of smoke. The first press conference Wednesday morning featuring city and county officials — not Bass, who was still not back — was held two days too late. Despite local forecasters raising the alarm on Monday morning that the week would bring a "LIFE-THREATENING, DESTRUCTIVE" windstorm, "about as bad as it gets in terms of fire weather," there had been no press conference detailing how the region was coordinating for this unprecedented event. Similar press conferences ahead of August 2023's Hurricane Hilary or before the winter storm of February 2024 were accompanied by emergency alerts notifying everyone with a phone with updates on potentially deadly wind and flooding. The city's first press release detailing "preparedness measures ahead of anticipated dangerous windstorm" went out Tuesday at 10:56 a.m. — after the Palisades Fire had started.

Some electeds valiantly updated their constituents, but with the mayor gone, the unified response seemed to have vanished as well. The utter silence from Bass for over 24 hours as she made her way home to LA only compounded the crisis. She didn't have anything to say after she landed either. She later claimed she was on a military plane and in constant touch with local officials. Why wasn't she calling into Fox 11, too? Heck, why wasn't she calling us? She should have somehow still been in our face two times a day.

The lack of centralized coordination led to chaotic mistakes. After officials casually mentioned declining water quality in interviews, a Notify LA alert went out warning of a "boil water notice in your area" which was reported by many outlets as "all of LA County." This nearly incited widespread panic until a second alert clarified "ONLY in zip code 90272 and nearby communities North of San Vicente." LAUSD, LA County's most effective tool to signify a serious disaster and keep everyone at home, once again struggled with a weather closure call. The district provided zero updates to families all yesterday morning while keeping most schools open, forcing staff to scramble as they navigated their own evacuations. Then LAUSD created mass confusion by closing about 100 schools before finally announcing all schools would be closed Thursday. The right choice, and hopefully Friday, too.

The irony here is that the emergency response to the fires themselves has been exceptional — not a single death has been reported in LA city due to fire! — but the communication with the public has been so abysmal that it's been hard to demonstrate the effectiveness. As hurricane-force winds shuddered homes across the region, keeping everyone up late Tuesday night, Caruso was able to swoop in due to the growing sense that no one was in charge. I'm not being glib when I say that LA's leaders demonstrated more situational awareness for the "traffic nightmare" on the first night of the World Series than they did for this real-life nightmare.

Once again this is a story about cooperation. It's about actually locking arms. It's the same story I write over and over about how the lack of regional goals is hampering LA's ability to get it together for its megaevent era. It's the same reason why we can't work across jurisdictional lines to build housing, green our schoolyards, repair playgrounds, bury our power lines, pick up trash, plant trees, and design streets that don't kill 300 people every year. Now, on top of all that, we must make an actual plan, as a region, to prevent this from happening again. We must come up with entirely different ways to build our neighborhoods and completely rethink where we live, and maybe, instead of evacuating next time, shelter in place. The Palisades Fire, which has destroyed the most valuable real estate in the country in an insurance market held together with toothpicks, is likely to become the costliest fire in U.S. history. And, in less than two weeks, the federal government will turn its back on our recovery. Thousands of families will be displaced for months or years. But what usually happens after extraordinarily destructive urban fires is that many of the people who lose their homes don't return. Our communities, still fragile from the pandemic, are on the edge of collapse. We have to bring them all back from the brink. We can't leave anyone behind.

Standing in front of the Palisades Village Starbucks yesterday, its blown-out arched windows evoking ancient Roman ruins, Councilmember Traci Park, the chair of the council's Olympic and Paralympic committee, took a cue from Caruso to further politicize the fire's destruction. "The demands that we are putting on our public safety resources is absolutely untenable," she told NBC LA. "And as we look forward to the World Cup in 2026 and the Olympics in 2028, this is a painful and tragic reminder of how much work we have ahead."

What? No, that's not the megaevent takeaway here. Here's what residents should ask themselves when surveying LA's ashen neighborhoods: if our leaders haven't yet put together a coherent strategy for something we supposedly want to happen in LA in three years, how can we believe that they're going to put together a coherent strategy to address the worst-case scenario that confronts us now?

On Wednesday night, just as the situation felt tenuously improved, another fire sparked near Runyon Canyon, triggering the evacuation of much of Hollywood. It was the closest to us yet. I could tell exactly when it started because my eyes started to prickle; I haven't been able to wear my contacts for days. I watched the evacuation gridlock along yet another stretch of Sunset Boulevard, frustrated that the members of our Metro board weren't encouraging people to take the subway that was free, operating on schedule, and probably the fastest way to safety.

But where is safety? When I first stepped outside Wednesday I found a charred page from a Westways magazine — a Pennzoil ad, a bit too on the nose — in our backyard. At the time, the nearest active flames were 15 miles away. As I photographed it, I wondered how recently it had been on fire. Maybe it was still smoldering as it landed on the woodchips behind my house. Then a gust of wind blew it out of my hand and onto my neighbor's roof. 🔥